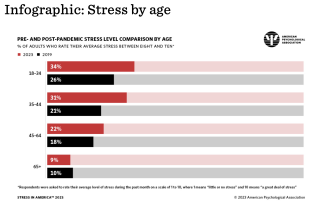

We have known for a long time that adolescents experience a lot of stress and anxiety, but what we didn’t know is that emerging adults, especially those in Gen Z, are extremely stressed and feel isolated and lonely. A recent survey by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) labeled Gen Z as the most stressed generation.

Our 2020 survey shows that Gen Z teens (ages 13–17) and Gen Z adults (ages 18–23) are facing unprecedented uncertainty, are experiencing elevated stress, and are already reporting symptoms of depression (APA, 2020).

And, according to APA’s 2023 survey, A Nation Recovering From Collective Trauma, Gen Z rates the following as significant life stressors:

- Money, 82 percent

- Health-related stressors, 82 percent

- The economy, 72 percent

- Housing costs, 70 percent

The survey found that the emerging adults of Gen Z are the most stressed-out generation in the post-pandemic era.

Source: American Psychological Association/Used with permission

Who Are Emerging Adults?

The stage of emerging adulthood was first proposed by Jeffrey Arnett (2000) as a distinctly different stage of development from that of adolescence and young adulthood. It is the period of development spanning the ages of 18-29 that most individuals in Western cultures experience. “Across industrialized societies, emerging adulthood is a period of many changes in love and work, but most people settle into enduring adult roles by about age 30” (Arnett, 2007, p. 72).

Who Are the Members of Gen Z?

According to the Pew Research Center (Dimock, 2019), Gen Z comprises individuals born between 1997 and 2012. There are 68.58 million individuals in this generation. Gen Z is more racially and ethnically diverse than previous generations, made up of 52 percent white, 25 percent Hispanic, 14 percent Black, 6 percent Asian, and 5 percent Other (Parker & Igielnik, 2020). Gen Z is on track to become the best-educated generation to date. Gen Z are emerging adults.

Source: Cottonbro Studio/Pexels

What Is Overparenting?

Overparenting is sometimes called “helicopter parenting”. It occurs when a parent over-nurtures their child by doing things for them that they should be doing for themselves, making decisions for their child, especially when the child is old enough to make those decisions by themselves (Clarke and colleagues, 2014). Overparenting involves high control, protection, and over-involvement in their child’s life. Overparenting can occur at any stage of a child’s life.

It is seen as particularly problematic during emerging adulthood when the child is no longer a child but is striving to become an independent individual with a separate identity from their parents. Overparenting tends to make the emerging adult overly reliant on a parent to make decisions. It also robs the emerging adult of learning valuable life skills, making adulting very difficult.

Let me share a true story. During their senior year, psychology majors at my university are required to complete a full semester 450-hour internship. They interview for each position, which gives them real-life job search experience and skills. One of the site managers shared this story.

At the end of the interview, she asked the prospective intern, “Do you have any questions?”

She replied, “No.”

And then she said, “Mom, do you have any questions?”

Unbeknownst to the interviewer, the student interviewee had her mother listening to the interview on her phone. And then, her mom began cross-examining the site manager. She even called the site manager afterward to find out why her daughter didn’t get the position. I am sure this mother had good intentions, but in the long run, she robbed her daughter of valuable life skills.

Overparenting, Loneliness, Social Anxiety In Emerging Adults

Chengfei Jiao and colleagues (2023) published a recent study that found overparenting to be a risk factor for emerging adults’ well-being. The researchers investigated the association between overparenting, loneliness, and social anxiety in 287 emerging adults.

Parenting Essential Reads

Participants completed an online survey two times, separated by a 12-week interval. The emerging adults completed a series of scales that measured the following:

- the overparenting behavior of their primary parent

- an emotion regulation scale

- a loneliness scale

- and a social anxiety scale

Findings

Relational overparenting by a primary parent was linked to increased feelings of loneliness, social anxiety, and difficulty in emotion regulation. Relational overparenting occurs when a parent controls the emerging adult’s relationships.

1. Increased feelings of loneliness (e.g., lack of companionship, feeling left out, feeling isolated from others, feeling like there’s no one to turn to, unhappy about being withdrawn).

2. Increased social anxiety (e.g., difficulty making eye contact, uncomfortable interacting with people at work, getting tense when alone with a person or meeting an acquaintance on the street, difficulty talking with others, especially when they disagree, attracting attention to oneself).

Negative feelings and confidence in one’s ability to form and maintain interpersonal relationships become a major stumbling block for emerging adults to make meaningful connections.

Source: Ron Lach/Pexels

3. Living arrangement and social anxiety. Those emerging adults who lived at home with their parents reported higher levels of social anxiety compared to those who lived with roommates or a romantic partner.

Overparenting appears to stifle emotion regulation. Parental socialization occurs daily when living at home. The emerging adult’s self-regulation of emotions, thinking, and behavior is suppressed by interacting with parents every day.

4. Difficulty in emotion regulation. The emerging adults in this study had difficulty regulating their emotions. Individuals who have poor emotion regulation report feeling overwhelmed and often have emotional angry outbursts. Poor emotion regulation can cause trouble in developing and maintaining relationships.

5. The following were not linked to loneliness, social anxiety, and emotion regulation:

- Financial overparenting (e.g., the parent keeps track of credit/debit card expenditures),

- academic overparenting (e.g., the parent tracks grades),

- and health overparenting (e.g., the parent tracks exercise schedule).

What’s a Parent to Do?

Parenting your Gen Z adult child has many challenges. There’s no operating manual. There’s no 100 percent right or wrong. Here are a few suggestions that may help parents and emerging adults navigate the bumps in the road on the way to becoming an adult by not overparenting:

1. Let them fail. That may sound harsh, but it is necessary. Don’t step in and rescue your children every time one feels the least bit of discomfort. Letting them fail is often difficult for a parent because it means a new pattern of behavior, and patterns are automatic.

They are difficult to change. As a parent, every time your infant banged their head or scraped their knee, you picked them up, soothed them, and put a bandage on their sore, and that was good and necessary.

As they grew older into an emerging adult, the pattern continued. For every problem, issue, and discomfort they experience, you jump in and rescue them, fix it, and try to relieve them of their discomfort. This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t step in and provide parental support if something very serious is going on, but too often, we do this for them when they can solve their problems.

Life’s biggest lessons are learned from our failures if we sit down and examine what went wrong and then make a new plan to address the issue.

I think of my father’s wisdom when we were little. When he wanted to take a nap, he would tell my brothers and me, “Don’t bother me unless there is blood.” In other words, you boys can work out your issues. And we did.

2. Ownership of the problem. Does the parent own the problem or the child? It is important to recognize who owns the problem because different skills are required. If the parent is upset about something the child has or has not done, the parent owns the problem.

If the child is feeling anxious, lonely, upset, angry, or frustrated about something, the child owns the problem. If the child owns the problem, it is your job as a parent to listen.

3. Listen more, talk less. Most of us think we are good listeners. Probably not. It is important to regularly assess your listening skills. As a general rule, listen more and talk less. (Note: If you search the Psychology Today webpage, you will find excellent posts on listening).

Go forth and parent, but don’t overparent.

Practice Aloha. Do all things with love, grace, and gratitude.

© 2023 David J. Bredehoft