“Tis harder knowing fear is due / Than knowing it is here,” sings neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux with his band The Amygdaloids. The song, an adaptation of Emily Dickinson’s poem “While we were fearing, it came—,” communicates some of LeDoux’s key insights about the brain and emotions chronicled in a new documentary, “Neuroscience and Emotions: The Life, Work, and Music of Dr. Joseph LeDoux.”

The documentary highlights the profound influence of the renowned neuroscientist on research and clinical practice. During the early 1970s, emotion was dismissed by most neuroscientists as too fuzzy a topic, but LeDoux’s mentor, Michael Gazzaniga, known for his research with split-brain patients, encouraged Ledoux to pursue the topic.

It was a risk. But LeDoux’s research played a big role not only in generating new knowledge; it helped make emotion a respectable topic in neuroscience. LeDoux is well-known for his work on the amygdala’s role in the making of emotion—though his ideas about that role are often misunderstood.

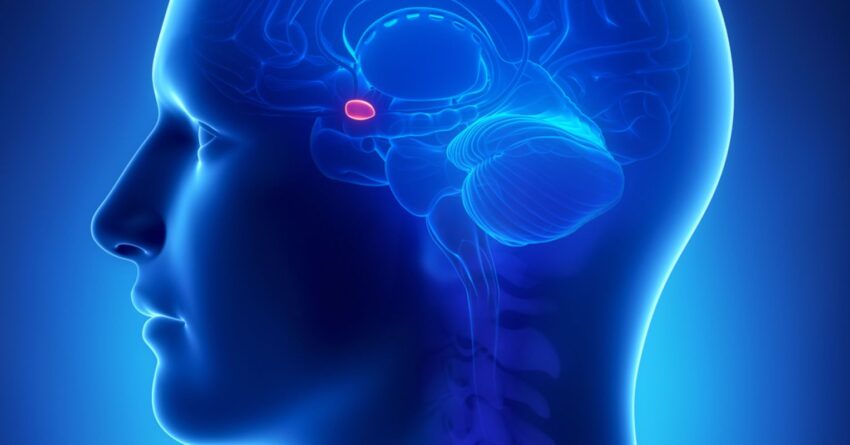

Ledoux didn’t set out to study the amygdala. In his early research with rats, he observed that when exposed to a lot of stimuli, their sensory systems connected with their motor systems. For example, if a sound is threatening, a rat—or any animal, including humans—might freeze, its heart rate and blood pressure increasing. In tracing the connection between the sensory and motor systems, LeDoux and his colleagues discovered the amygdalae, two almond-shaped cell clusters located near the base of the brain. Sensory information, he observed, passes through the amygdalae and is then relayed to motor systems.

While the amygdala plays a role in the making of fear, anxiety, and other emotions, it is not the brain’s “fear center,” as it’s often misconstrued. In his words:

“The amygdala has long been thought of as a fear center. But if by fear we mean the mental state, the feeling, of fear, it is not the amygdala that is responsible. The amygdala detects and responds to danger. Fear is a cognitive interpretation of the situation externally and internally.”

The amygdala works like a hub between brain systems, among many, in the brain’s generation of emotion—including systems for blood pressure, heart rate, stress hormones, and freezing. LeDoux’s early research demonstrated the relations between these systems and the rest of the body’s responses to threats.

“What gets lost,” he says, “is that connection between that feeling of fear and responding to threat.” Fear—and other mental states—are cognitive responses to the stimuli detected by the amygdala. The interactions of the various systems involved, he argues, create a working memory circuit that becomes the feeling of fear.

He didn’t know he’d become a neuroscientist, but LeDoux had his hands in the brain early on. He grew up in small-town Eunice, Louisiana. His family owned a meat shop. His job was to pick the bullets used to slaughter the cows from their brains. As he describes it, he gained an intimate familiarity with brains, without the language to describe it.

When LeDoux joined Gazzaniga’s lab and began his pursuit of a Ph.D. in neuroscience, he had an undergraduate degree in marketing and no real experience in science. But he had a spark and was admitted. Nobody could have known just how influential LeDoux would be on the ways neuroscientists and psychologists understand emotions—especially fear and anxiety.

Late in the nineteenth century, William James proposed an idea similar to LeDoux’s: that our bodies respond to stimuli before they become conscious. “For me,” LeDoux explains:

“much more is involved in the cognitive interpretations: memory schema that integrates information about the situation, about what danger and fear are, about past dangers you’ve had, what the body felt like. Schema are the preconscious template from which the feeling of fear arises. Because no one else has your schema, no one else has your fear. And just because we can translate the word fear across languages does not mean that people in different cultures have the same feeling of fear. Your personal experiences and the schema that result are thus in part shaped by your culture (and subculture/subcultures).”

Neuroscience Essential Reads

If fear and anxiety were simply products of the amygdala, it would be much more difficult to change our relationship with them—through, say, exercise, psychotherapy, exposure therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, yoga, meditation, or somatic practices. LeDoux’s research has implications for all these therapeutic modalities. In his personal life, music has played a therapeutic role.

“Neuroscience and Emotions” also chronicles LeDoux’s music career, demonstrating the close affinity of Ledoux’s research and his music. He and his bandmates refer to their genre as “heavy mental.” Their songs are about the brain, psychology, and mental disorders. But the more interesting affinity is the relation between music and emotion.

The documentary’s portrayal of music in LeDoux’s life is moving and surprising. LeDoux has played music all his life, but he got more serious about it after he experienced a personal tragedy. In the documentary, he discusses how music brought him solace and stimulation.

While music doesn’t diminish grief, it can help a person establish a new relation to the emotion. Music—writing it, playing it, listening to it—can usher what’s unconscious into consciousness. When a rat hears a tone, it responds with its body. The same is true of humans. Though LeDoux doesn’t study the relation between music and emotion, he enacts it through his own music.

After decades of research and four influential books on the brain, emotion, selfhood, and the evolution of consciousness, LeDoux has decided he’s collected enough data. He plans next to write about “the interconnection of brain systems—a topic still not well understood, but crucial. As LeDoux’s research has shown over time, no system in the brain acts on its own, but in relation to others. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that he’s turning his attention to these interconnections.

If LeDoux wants us to know one thing, it’s that the amygdala is not a fear center. Instead, it’s an important piece in those interconnections. In Dickinson’s poem that LeDoux adapted to song, she details the cognitive gyrations of fear that make feelings of fear and anxiety so menacing. Dickinson, generally ahead of her time, explores the vicissitudes of fear states. Dickinson, like Ledoux, reminds us that these painful feelings, like all feelings, change with time and experience.