Dr. Henri Laborit, the inventor of the first neuroleptic, devoted years of his career to the study of aggression. In a famous experiment, he subjected rats to stress. This experiment, like Stanley Milgram’s electric chair “obedience” experiment, would likely be questioned and possibly not allowed by ethics committees today. But its findings are fundamental.

Electric shocks cause severe pain to rats, as they do to other animals. Laborit designed a rat cage with two compartments separated by a door. A metal floor allowed electric shocks to be delivered alternately in compartments A and B. The cage had a beeper and a light. There were three conditions for the experiment.

In the first condition, the door between the compartments was open. At regular intervals, the light turned red, a warning beep sounded, followed by an electric shock in the floor of one compartment (say: A). The rat quickly learned to flee to the other compartment (from A to B) as soon as the warning sounded.

Then came the next warning; this, time the shocks occurred in compartment B. The rat learned to change compartments alternately as the shocks changed compartments. Thus, the rat learned to avoid the shocks by always changing compartments when the warnings came.

After a week of this treatment (7 minutes a day), the rats stayed perfectly healthy. They learned to control the situation by fleeing.

The second condition was the same as the first, except that the door remained closed. The rats could not escape the electric shocks even after the warning. They could only stand, stressed, as they experienced the shock and subsequently developed anxiety. After a week of this treatment, the rats showed serious symptoms of somatic disorder. Their skin and fur were in poor condition; they lost weight and developed stomach ulcers and chronic high blood pressure.

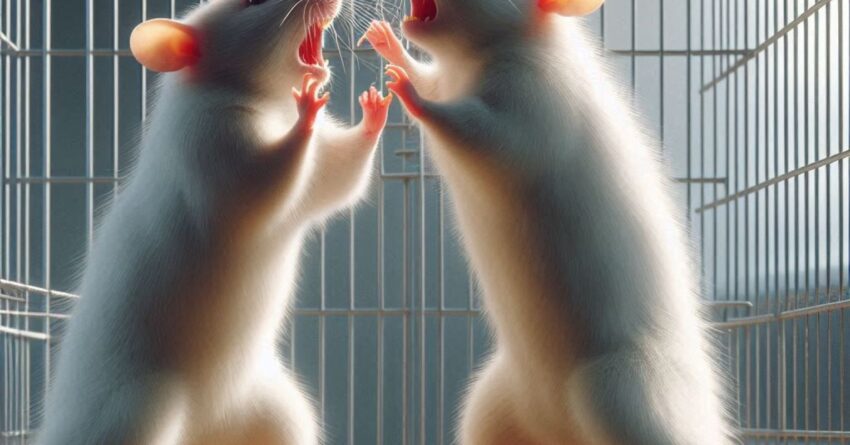

The third condition was similar to the second: predictable but inescapable electric shocks, door closed. But this time, there were two rats in the same compartment. When the warning came, the rats started fighting each other and stopped after the shock. Interestingly, after a week of this treatment, the rats, apart from the bites and scratches resulting from the fights, appeared to be in perfect health!

Rats fighting as they experience the electric shock

Source: OpenAI/Dall-e

These three reactions can be seen as comparable to flight, fight, or freeze. The stress caused by the threat can be transformed into action—whether that action is running away (flight) or attacking (fight). If no action is possible, there is inhibition (freeze), which could lead to psychosomatic disorders, as in the second condition where the symptoms are not directly caused by the shocks.

These results are sobering and may even suggest that when you are stressed, attacking someone else can bring relief. This could explain much of the aggressive behaviour we see—from people who become aggressive when they are stressed at work, to the driver who, when he almost ran you over, insulted you instead of apologizing, perhaps as a way to cope with the huge rush of stress he just experienced.

At a societal level, it could also help explain why it is so easy for cynical politicians to channel the frustration and anger of those who are experiencing harsh living conditions toward some scapegoat (often foreigners, believers of a different religion or ideology, any kind of minority, or whatever “other”). It makes them feel better.

What Explains This Phenomenon?

Evolutionary psychology would argue that this behaviour is partly the result of the evolution of the species. In the wild, much stress comes from aggression by another animal, such as a predator or a conspecific competing for the same resource.

Responding by fleeing or fighting, whichever seems best, is an efficient response. Those individuals who used these strategies increased their chances of survival (and reproduction), so the mechanism was passed on to their descendants and became systematic in the species.

According to Laborit, since the nervous system is designed for action, if you inhibit external action (the flight or fight), you harm yourself (with psychosomatic disorders). It is as if you are deflecting aggression against yourself.

But in reality, the situation is more complicated. First, there are psychological defence mechanisms other than running away or attacking someone else to deal with stress: denial, sublimation, etc. Then, neuroscience is now discovering the complex system of dozens of interwoven mechanisms involved in coping (biochemical cascades top-down, bottom-up, transverse, etc.) For your body, preparing for action with all this biochemistry and emotions, and then inhibiting action, is like preparing a meal for guests and then being told the invitation is cancelled. It creates a mess.

Neuropsychology is still struggling to understand how physiological processes translate into emotions, moods, drives, etc.—and vice versa, the biochemical nitty-gritty of the old body/mind duality. We have only scratched the surface of the complex relationships between the nervous system and the immune system, for example; but now we know they communicate and influence each other—as psychosomatic medicine had anticipated, albeit in simplistic models.

What You Can Do With This Knowledge

But while the mechanisms are not yet fully understood, the sad fact remains that frustration tends to produce aggression as a way of coping. What does that mean for you? I argue that the conclusions to draw from this are fourfold:

- If someone is aggressing you, first try to understand their motive. Often it is because they are stressed. Knowing why will help you deal with the problem (this does not, of course, apply to predatory aggression such as mugging).

- Yes, aggression can give you temporary relief. But it will not solve the problems that are at the root of your frustration and anger. Violence tends to create more problems.

- Flight is a good temporary solution, but it seldom solves the problem.

- Finally, remember that passive coping, turning your aggression against yourself, can have disastrous long-term somatic consequences.

For years I have been discouraged by Laborit’s findings because they do not bode well for a world in which stress is increasing with the scarcity of resources and now with climatic events. Will all this end in generalised war, as it is already happening in many parts of the world?

That was until I had an experience that was an epiphany: there is another, fourth way to deal with stress—a productive way so obvious that one wonders why it is not systematically applied instead of blindly following our instincts to flee, attack, or inhibit. I’ll discuss that in my next article. Stay tuned.