“Can I ask you when you first knew your son was autistic? I’m kind of worried about mine.”

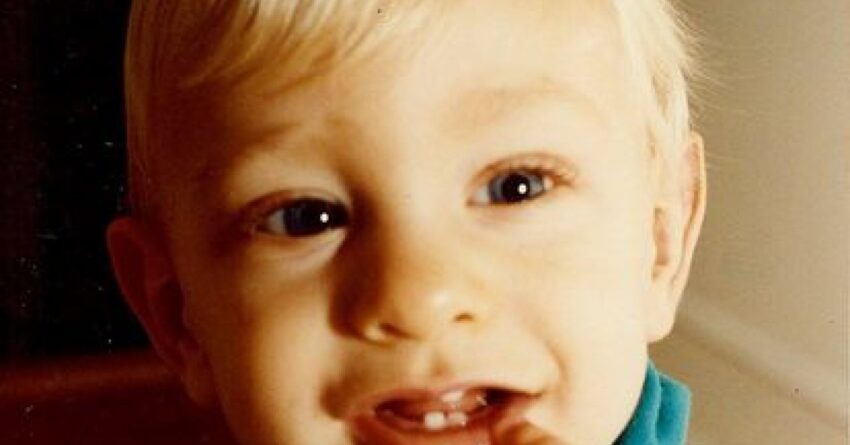

I get this question fairly often from young mothers. When did I first know? For me, it was from the very beginning. Nat was my firstborn and I had almost no experience with infants. But something felt different. He had an alarming startle reflex. But so do many infants. But every time he was startled, there was this tender yet scared feeling I had. I could not reassure myself that he was fine. Then as he grew, I remember describing a frequent feeling I had, that he didn’t really seem to need me, which was ridiculous because of course he needed me — he was a baby. But the feeling persisted into his first and then second year. He seemed emotionally self-sufficient. My heart often hurt back then, even when I laughed.

Thirty-four years later, I no longer feel that way, for the most part, except when things go wrong for Nat and I am hit in the face with his profound vulnerability and his utter dependence on others. “Things going wrong” can be anything from a sudden schedule change to a different staff person at his program, to the change of seasons, or a power failure. I always carry around a sense of waiting for that other shoe to drop. My days hinge on waiting for the phone to ring. The fear is not for me, but for him and others who care for him. I don’t want anyone to be hurt, sad, or angry, and I do not want him kicked out of his program.

So what do I say when a young mother is worried that her child might have autism? I have to be careful. I’m not a psychologist. I don’t want to diagnose anyone, or worse, misdiagnose them. But because I know that a missed diagnosis is worst of all, not only because the child misses out on early education and therapeutic interventions, but also because of the potential for trauma. Many people on the spectrum say that their eventual diagnosis was a huge relief because they finally understood their differences from others.

Be Empathic; Connect

When I talk with young mothers, I try to tap into my advocate self—my professional self. I try to quiet down my younger self. I remember that even with all the evidence—odd, repetitive language, long bouts of crying, little interest in people—still I resisted taking Nat to be evaluated. He missed out on early intervention. So I have to take care not to feed into a young mom’s anxiety over her child’s development and empower her to get that referral. This is not easy, though, because their anxiety pierces right through me, as I remember my own feelings of fear around my son Nat — fear that something was wrong and terrible things were going to happen that I couldn’t stop. My sense of inadequacy threatened to swallow me up back then, heightened by the company of other young moms and their seemingly perfect children.

Now I know that no child is perfect. Things happen to each of us in our lives — scary, difficult situations beyond our control. In my son’s case, autism was the thing that was happening to him. And he was only a toddler. That experience, the confusion and the helplessness, as well as being so stuck, so unable to take action, still haunts me three decades later.

So I gently tell them that we never know what these little humans of ours are going to become. All bets are off. I reassure them that that’s okay, we learn how to parent them, no matter who they are. This child is a brand new person and we have the honor of watching them become themselves. So I encourage them to see their child in this light, and not to compare them to anyone else, though I know that is hard to do.

Let Them Get It All Out

I try to set up a safe, nonjudgemental moment for a mother to tell me what is happening that makes her so worried. I do ask (gently) about developmental milestones, but I also know that everyone is different and that you can’t go by any exact template. I let them share videos of their kid and I am quick to point out anything positive or adorable there.

When they pause and take a breath, I congratulate them on being such an engaged and loving mother. But I also encourage them to think about what they know about their child and tune in to that. “Don’t let anyone tell you that you are ‘just a worried mom.’” Parents know their kids better than anyone and it is their job to push their professionals to share the responsibility of this child’s development. In my case, eventually, I felt certain enough that I went into my pediatrician’s office and presented her with a list of the milestones Nat had not met. She had to refer him after that.

Encourage a Referral and Support

I doubt anyone has ever regretted getting their child early intervention. As hard as getting the diagnosis is, taking action and watching your child learn from the therapies is incredibly affirming and strengthening. The research has found that most people benefit from early education, autistic or not. “Getting therapy does not automatically mean the child has a disability,” I say. And I think to myself, also, having a disability is not the end of the world, it is just a challenging and different world. But the young anxious mom is not ready to think that way.

I also encourage those I talk with to join some sort of group for young moms who are worried about their kids. Because, whether or not there is a reason for their concern, the best thing is not to be isolated, like I was. The moment I found a support group, my world changed. I found parents like me, and I even got a glimpse into what an older autistic person might be like. This was life-saving for me. And the stories I learned that I was able to bring back to my husband helped him deal with it, too.

I tell them that they have a lot of time to get used to whatever is in store for their kid. I tell them how worried I used to be about what Nat’s life would be like and what he would be like. Now I smile because it has turned out okay for him. And I hope that they can see the hope that I see, because having autism or having an autistic child is no tragedy, not in the least. It is excruciatingly hard but it is not tragic. The tragedy is not getting the child the help they need as soon as possible. The worst thing is not teaching them how to be their best self.