Source: LuchschenF / Shutterstock

“Benzodiazepines have well-established acute adverse effects on cognition,” write Netherlands-based Erasmus University professors of Epidemiology, Radiology, and Neurology in the latest issue of BMC Medicine. Benzodiazepine use is also “common,” they add, particularly in older adults, but its “long-term effects on neurodegeneration and dementia risk remain uncertain.”

In their sizeable (5,443-person) open-access study, “Benzodiazepine use in relation to long-term dementia risk,” Ilse vom Hofe and colleagues draw from the population-based Rotterdam Study (57.4 percent women, mean age 70.6) and from Dutch medical records documenting benzodiazepine use since 1991.

Among their most notable findings: almost half (49.5 percent; n=2,697) of all participants had taken a benzodiazepine over the previous 15 years. 46.8 percent of the drugs were prescribed for anxiety and 33.5 percent for sedation/insomnia.

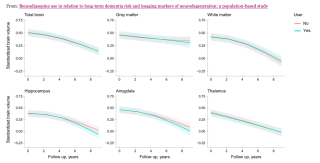

Benzodiazepine use in relation to long-term dementia risk

Source: Hofe et al, 2024 / Creative Commons

After a follow-up interval averaging 11.2 years, the researchers also found that 726 of the 5,443 (13.3 percent) had developed dementia. Equally notable, fMRI imaging showed that continued benzodiazepine use was “associated cross-sectionally with lower brain volumes of the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus,” and “longitudinally with accelerated volume loss of the hippocampus and to a lesser extent amygdala.”

Writing about the findings, Emily Cooke extrapolated that the new study “suggests that long-term benzodiazepine use may shrink parts of the brain involved in memory and mood regulation.” In so doing, it would corroborate research documenting the same problem from the 1980s and 1990s, when benzo-related brain damage first made national, then international, news.

In 1982, to cite one of the earliest high-profile examples, Malcolm Lader, a British professor of psychopharmacology, reported that brain scans of a small group of patients who had taken diazepam for several years produced evidence suggesting that their brains had been damaged. Although warning that his preliminary findings needed more research, Lader pointed out that the results suggested that the brains of regular benzodiazepine takers were damaged and shrunken when compared to those of people who had not taken benzodiazepines.

More recently, in 2023, when a total of more than 30 million Americans reported taking benzos, a comprehensive survey of 1,207 users found that 76.6 percent reported symptoms after discontinuation that persisted for “one year or longer.” More than half of respondents (54.4 percent) reported suicidal thoughts or had attempted suicide.

A concerning pattern

Although the latest findings partly corroborate this pattern, the researchers in the Netherlands conclude that “overall use of benzodiazepines was not associated with increased dementia risk.” Regarding the more than one in ten (13.3 percent) that had developed dementia in their systematic review, that is, the researchers do not determine conclusively that benzodiazepines had been a clear or leading cause, leaving the relation as one of “association”—even, in the case of prescribing for anxiety, a “strong” one.

Commentary

As dementia also is a condition in which the brain loses mass, frequently of the frontal and temporal lobes, it is critical to study dementia risk and brain shrinkage from benzodiazepines to differentiate their effects. The researchers’ caution in pronouncing a clear risk of dementia from long-term use of benzodiazepines may also be tied to study design. It nonetheless risks downplaying their own significant finding about brain shrinkage: “Current use [of benzos] at baseline was significantly associated with lower total brain volume as well as volumes of the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus [emphasis added].”

That this finding is made less important than dementia risk remains perplexing, because, as they note in the article, “results from two recent meta-analyses (2021 and 2021) suggest that use of benzodiazepines is associated with higher dementia risk, indicating that the harmful effects of benzodiazepines might outweigh any protective effects.”

Psychopharmacology Essential Reads

Comparable reviews and meta-analyses

In 2021, in a systematic review of reviews asking “Is there a link between the use of benzodiazepines and related drugs and dementia?,” a comprehensive search of 877 records, five of them meta-analyses, found that “data…suggest an association between the use of BZDs/BZRDs and increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults.”

Also in 2021, in the systematic review and meta-analysis “Use of sedative-hypnotic medications and risk of dementia,” Asma Al-Dawsari at Strathclyde’s Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences and colleagues in Saudi Arabia and South Africa found that “all investigated sedative-hypnotics showed no association with increased risk of dementia except for” benzodiazepines. When studies with potential reverse causation and confounding were ruled out, “the observed association with BZDs did not persist, leading the researchers to conclude that the “association needs to be assessed carefully in future research.”

When invited to comment on the latest findings, Martin Plöderl of Salzburg’s Paracelsus Medical University raised a number of concerns: “The main result is a Hazard-Ratio of HR [95 percent Confidence Interval]: 1.06 [0.90–1.25]), which means that the uncertainty includes a 0.90-times reduced risk of dementia with benzos, or an up to 1.25-times increased risk (25 percent increase).”

Plöderl adds:

The researchers interpreted non-significant results as having “no, or unclear, association,” which is problematic. Particularly as the confidence interval includes a 1.25-fold increase of dementia risk at any time-point, which may be considered clinically significant. In addition, they found a dose-dependent effect in some subgroup analysis, which is cause for concern, especially in light of the findings of the fMRI results. Finally, as the authors discuss in their section on study limitations, they used a binary diagnosis of dementia (i.e., present or not present), rather than a preferred dimensional measure of cognitive decline. The authors also did not present a Kaplan-Meyer curve, where you can see how the groups separate over time.

Past and recent meta-analyses of benzodiazepines’ long-term sequelae continue to urge consideration of the drugs for brain shrinkage as for dementia risk. The data remain ambiguous, and the extent of harms extrapolated still unsettled.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7, dial 988 for the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.