Anxiety seems to be rising everywhere these days. Research on adult anxiety conditions indicates significant increases over the past decade—not just post-COVID—particularly among younger adults.1

And as recently as this week, the U.S. Surgeon General wrote a rare opinion piece in the New York Times recommending that social media platforms include mental health warning labels in response to rising levels of anxiety and depression among youth.2 Faced with growing political dissatisfaction, international conflicts, rapid technology changes, and a 24/7 news cycle updating us on every new crisis and concern, heightened anxiety may seem inevitable.

Yet whenever our personal or collective futures appear filled with potential calamity, reflecting on lessons from our nation’s history may be a potent remedy. This is one of my favorite history lessons, containing a powerful moral for modern times.

In the late 19th century, the world’s dominant superpower was still Great Britain (the U.S. assumed this role post-World War II) and the world’s largest newspaper was the London Times (not the New York Times like today).

In 1894, the front page of the London Times proclaimed that we were facing a major societal threat3—a threat that could jeopardize cities and halt societal progress as we knew it. Unlike today, however, this threat wasn’t a climate crisis, a pandemic, or even a war.

The threat was horse manure. In 1894, you see, millions of people traveled to major cities like London and New York every day on horseback. Horses were a ubiquitous part of travel, the transportation of goods, and city life, with horses numbering in the tens of thousands in larger metropolitan areas.

And horses create a lot of manure. So much manure, in fact, that mathematicians projected that London would soon be buried under up to 10 feet of horse manure if something dramatic wasn’t done.

Thus, a convention of leading scientists and politicians gathered in 1898 to decide how to preserve cities and protect themselves against this societal threat. History suggests, unfortunately, that no solution could be identified, creating good reason to be anxious for those knowing about the problem.

Meanwhile, a few thousand miles across the Atlantic Ocean, an industrious man named Henry Ford had just turned 30. Henry wasn’t invited to this important convention. But just a few years later, he would introduce the Model T and the world would quickly forget that just a decade prior some of the most powerful people in the world were worried about horse manure.

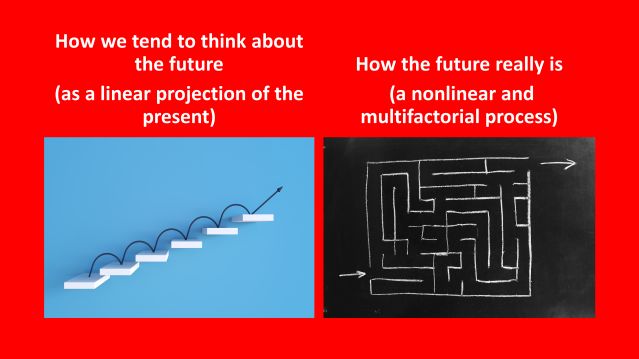

How we think about the future determines our emotional response

Source: Thomas Rutledge (stock images from PowerPoint)

Moral of the story? When I find myself worried about the future, I pause and ask myself if this is a “horse manure problem” (a problem based on the usually naïve assumption that everything is going to follow the same pattern going forward). More often than not, I find the answer is yes and I can more easily put the worry to rest.

Takeaways

- Add “horse manure problems” to your vocabulary. We all have these problems and they are more important to recognize than ever in the modern world.

- Remember the expression, “Worrying works—90 percent of the things I worry about never happen.” The reason this expression is true is that our anxiety system evolved to help us avoid acute life-and-death stressors such as predators. It did not evolve for modern chronic stressors such as paying bills and managing traffic. With our outdated anxiety software, we must learn to apply conscious strategies to manage long-term risks. Otherwise, our short-term anxiety instincts will rule the day and probably ruin our lives.