Source: Tero Vesalainen / Shutterstock. Used with permission

“Today, the existence of symptoms emerging after antidepressant discontinuation or dose-reduction is no longer questioned,” write Jonathan Henssler and colleagues at Cologne, Berlin, Freiburg, and Dresden universities, in the latest issue of Lancet Psychiatry.

That would be an outcome worth celebrating. Unfortunately, as the researchers acknowledge, “Medical professionals continue to hold polarized positions on the incidence and severity of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms, and the debate continues in public media.”

Argument and Controversy

Since the late 1980s, when SSRI and SNRI antidepressants were first licensed, argument and controversy has flared over how the condition is described, how long it can last, how severe it can get, how prevalent it is, and why it’s taken almost four decades of prescribing to answer such fundamental questions.

In an attempt to address the problem, Henssler and colleagues set about quantifying the incidence of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms and their average duration. They hoped to reassure clinicians and prescribers that their findings don’t cause “undue alarm.”

Unfortunately, they still do. While their meta-analysis yields important information about withdrawal symptoms, it is mostly based on short-term industry-funded studies that routinely downplay severity and, by definition, can’t assess longer-term outcomes—the precise factor necessary to quantify longer-term prevalence.

Estimating Nocebo

Henssler and colleagues looked at randomized controlled trials (RCTs), other controlled trials, and observational studies assessing the incidence rate of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms—also known as antidepressant withdrawal, antidepressant withdrawal syndrome, and protracted withdrawal syndrome (PWS or PAWS). Of the 6,095 articles screened, 79 studies (44 RCTs and 35 observational studies) covered 21,002 patients (72% female, 28% male, with a mean age of 45 years).

Of these, 16,532 patients had discontinued from an antidepressant, whereas the remaining 4,470 had discontinued from a placebo. The second group helps measure a nocebo effect among unmedicated patients, separating psychological from purely chemical withdrawal effects.

When both sets of evidence were factored in, the study authors found that the “incidence of at least one antidepressant discontinuation symptom was 0·31”—that is, affecting one in three—in most of the study groups assessed. When the nocebo effect was taken out, that number dropped to one in six, suggesting a substantial effect. They conclude, “We estimate the frequency of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms to be in the range of approximately 15 percent.”

That is substantially lower than in broadly comparable systematic reviews, where prevalence rates reached a weighted average of 56.4 percent from 14 relevant studies (2019), and 53.9 percent from six RCTS, representing 731 participants (2023).

Study Limitations

The numbers presented in the Lancet study are “meant to inform clinicians and patients about the probable extent of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms without causing undue alarm,” Henssler and colleagues contend, adopting terminology preferred by drug makers, sponsors of many of the trials reviewed.

Others have expressed concerns about the quality of studies supporting the review. In a thorough analysis, University College London scholars and withdrawal experts Mark Horowitz and Joanna Moncrieff caution, “First, the majority of studies included in the review were short-term studies conducted by drug manufacturers who have no incentive to detect withdrawal symptoms… [Second,] many of the studies were not designed to examine withdrawal and did so only incidentally or did not thoroughly assess withdrawal symptoms.”

If a study does not “systematically evaluate withdrawal effects,” Horowitz explained in a follow-up email, it is “bound to underdetect them. Only a few [of the 79 studies assessed] used a tool like the DESS. Some relied on chart reviews to see how many patients doctors diagnosed with withdrawal. Given that doctors are notoriously bad at diagnosing withdrawal, this is bound to undercount.”

Methods of Assessment

In one of the Lancet study’s key reports—whose 2,675 patients comprise more than 10 percent of its participant pool (21,002)—Fumihiko Okada at the Sapporo Mental Clinic in Japan identified patients described as manifesting withdrawal, though he provides no rationale for their inclusion or exclusion.

“No method is described at all,” Moncrieff stressed to me over email, “so we have no idea what the figures represent. The point is, this was not a proper study of withdrawal and it is extraordinary that this sort of report was considered as reliable evidence from which to calculate incidence rates.”

“The method of assessment of discontinuation symptoms in the included studies was very variable,” affirms Tony Kendrick, professor of primary care at the University of Southampton, in solicited expert commentary online. “Many of the studies included … were not set up to study antidepressant discontinuation as a primary aim, but were efficacy studies comparing an antidepressant versus a placebo for a depressive or anxiety disorder.”

“In close to half of the 79 included studies,” Kendrick adds, referring to information limited to the study appendix, “the period of taking the antidepressant was 12 weeks or less.… This is a serious weakness which is not acknowledged in the paper, as severe discontinuation symptoms would not usually be expected to arise after only a few weeks of antidepressant use.”

Finally, Kendrick concludes, “there was no public or patient representation on the study”—also known as “lived experience”—“which if present might have made the authors consider at greater length these weaknesses in the studies in terms of the durations of antidepressant use and the methods of assessment of discontinuation symptoms.”

The omission further adds to the likelihood of an undercount.

National and Global Implications

If the findings of the Lancet study are set alongside recent prescribing rates, where in England, 2019-2020, one-in-six adults in England was prescribed at least one antidepressant, representing 7.8 million people, we would find that half of them, 3.9 million, “have used them for more than two years—with 2 million people on them for more than five years. In the U.S., half of people taking antidepressants are on them for more than five years” (Horowitz 2023; Horowitz and Moncrieff 2024).

The lower incidence rate of 1 in 6 would affect roughly 650,000 people in the U.K., or a population almost the size of Bristol. The higher incidence rate of all groups combined, or 1 in 3, would double that, affecting roughly 1,300,000 people, or a population almost the size of Glasgow.

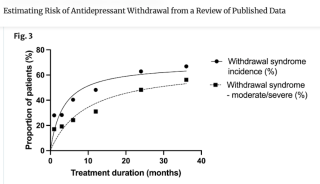

Withdrawal syndrome incidence detailing treatment duration and proportion of patients. Creative Commons License.

Source: Davies and Read 2019, reproduced in Horowitz et al, 2023

Earlier studies on withdrawal, from 2019 and 2022, determined that duration of use has a strong effect on risk of withdrawal and its severity (Horowitz 2023). Illustrated by data in the adjacent table, including the estimated incidence of withdrawal at 12 weeks, or three months, compared with at 30 months and beyond, the point underscores that a heavy reliance on short-term trials necessarily obscures and undercounts longer-term symptoms and their associated incidence.

Failing to adopt randomized controlled trials that study the long-term effects of antidepressant withdrawal will continue to undercount prevalence, severity, and duration—the precise number of those affected longer-term and the length of time they can, and do, experience symptoms, mild and severe.