I’ll come right out and say it: I’m anti-coping skills. The phrase triggers me almost as much as the chronic overuse of the phrase “triggers me” to mean “I don’t like it.” Being anti-coping skills might be a controversial perspective. But it’s really just my mildly rebellious response to the overreliance on pathology-worsening avoidance tactics frequently prescribed during the course of psychotherapy.

It’s one of my greatest pet peeves as a therapist when I ask a patient what they’ve done in previous therapy, and their answer is that they’ve been working on coping skills. I have a hard time understanding why that would take more than a session or two. Coping skills are pleasurable, relaxing behaviors we engage in to mitigate anxiety. Certainly not a long-term strategy for success in your battle with anxiety symptoms. There is a distinction between coping skills and risk-reduction behaviors (like calling a friend instead of relapsing into addiction or engaging in healthy exercise instead of self-harming), which I fully support.

I contend that you can’t cope your way out of anxiety because coping is anxiety avoidance, and anxiety itself is a symptom of avoidance. Like trying to put out a fire with matches. To be fair, I’ll admit that in high-pressure, time-limited situations, like before a job interview, we might all be wise to take a few deep breaths, go for a run, or remind ourselves that our success in the interview does not define our value as human beings (coping skills). But, if coping skills remain our approach to anxiety management after months (years?) of treatment, then we’re simply putting a band-aid on a wound that requires stitches.

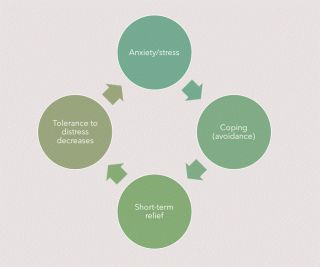

The Cycle of Anxiety

Source: Courtesy of Daniel Flint

So what’s to be done instead? Effective psychological treatment for anxiety can be accurately summarized as follows: clearly identify the scary thing, slowly and surely confront the scary thing, and continue to do so until the scary thing is not as scary. According to most empirical research, this roadmap is the core effective component of psychotherapy (Wampold & Imel, 2015; Ougrin, 2011, among many others). Whether it’s fear of spiders (understandable, if you ask me) and your psychologist recommends exposure with response prevention (ERP) or fear of crowds and your psychologist recommends cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for social anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and your psychologist recommends narrative exposure therapy (NET), the core mechanism is shared: that the scary thing (spiders, crowds, or memories) must be confronted until it’s not so scary anymore. Good therapy enacts this process in a supportive, empathetic, and genuine context.

Instead, what would therapy that focused primarily on identifying and practicing coping skills be communicating? The way to improve your anxiety is by avoiding it. There are few (are there any?) aspects of life where the easy/pleasurable route is the most advisable. And this approach to therapy almost implies that there isn’t a clear solution. But there is. The only way out is through working with your therapist on facing the scary thing head-on. Slowly, yes, have a plan for confronting your fears. If coping skills must be used, ensure that they are only being used to help you confront the fear instead of to help you avoid the fear.

Perhaps we should define and contrast confrontation coping with avoidance coping. I can confront my anxiety about my upcoming work presentation by practicing and thinking back on all the good presentations I’ve given in the past. Or, I could listen to music, watch TV, and take a bath every time I think about my presentation to cope with the anxiety. The latter perpetuates the psychopathology of avoidance and, ironically, increases the likelihood of a sub-par presentation and future low self-efficacy beliefs about my ability to present.

As long as therapy is particularly careful not to enable avoidance, I might be willing to reconsider my anti-coping skill stance.