Source: John Hain/Pixabay

This post is Part 2 in a series on emotional reaction and proactive choice. Read Part 1 here.

Before we can take steps away from reacting emotionally in favor of making proactive choices, we need to understand the science behind our reactions. Being aware of the processes that play a role here will help us to understand what is happening and why. With this information, we can move towards controlling how we manage our responses.

When we are emotionally triggered, our analytical processing mechanisms, situated in our prefrontal cortex and responsible for proactive choice, switch off. Our emotional processing mechanisms, situated in the amygdala and responsible for our fear response, switch on. Both mechanisms can not be active at the same time. The amygdala regulates the activation of our freeze-fight-or-flight (FFF) response when it senses danger without any conscious initiation from us, preparing us to flee to safety.

When activated, stress hormones—adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol—are instantly released into the bloodstream. They slow functions that are nonessential in an FFF situation, such as our digestive system; I bet you’ve never craved a steak dinner during a stressful moment. By doing so, energy is reserved for functions more critical to warding off danger. Our senses are on heightened alert; our heart beats faster in order to pump increased blood flow around the body, raising our energy levels as our muscles expand to help us move. Fast. Our focus becomes singular, clouding our ability to consider other variables in our environment, and remains so until our FFF response subsides.

In the event that a lion walks towards us, unguarded, our emotional processing mechanisms would be very helpful indeed. Generally, however, we do not face life-threatening situations such as these on a daily basis. Our fear response is activated, nonetheless, in exactly the same way whether we are emotionally triggered by a life-threatening situation or a relatively standard, mundane one in comparison.

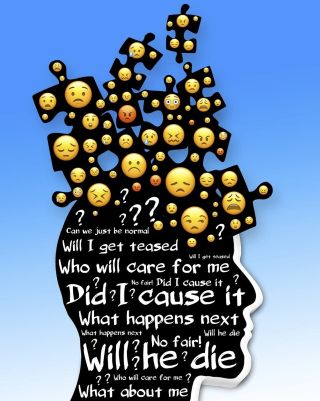

There are many different events that can be emotionally triggering.

Social interactions, for example, whether they be face-to-face or through social media, can be highly influential in the frequent activation of our FFF response. Individual interpretation of and the significance thereof applied to a social interaction determines how emotionally triggered we become. For example, after uploading a new post to Instagram and receiving fewer likes in comparison to a friend’s post, if you start to question your own popularity, you will spark feelings of inadequacy and insecurity. Imagine you call out to a friend walking on the other side of the road, and instead of responding, she continues walking. If you interpret her lack of response as a shun, it will trigger your emotional response, sparking feelings of anger and resentment.

If we compare the potential outcome of a lion walking towards us with an upsetting social interaction, is it best to allow our FFF mechanism to provide a disproportionate physiological response? Or could it be worthwhile for our emotional well-being overall if we take steps to learn how to switch it off? Remember, stress hormones obscure our focus and inhibit our ability to make proactive choices. Our FFF response may lead us to inaccurately interpret our needs whilst not only ignoring the needs of others but possibly jumping to conclusions about their motivations, which may get us into all kinds of trouble.

For neurodiverse individuals, this is exactly what happens.