What is the brain’s operating system? How many types of people are there in terms of basic patterns of mental function? We don’t really know.

What personality is and how many variations of personality types remains only partially understood. Some of the most familiar and popular personality tests fall short of statistical and scientific validity, no matter how much they capture our hearts and imagination.

Familiar psychological typologies—the Five Factor and the six-factor HEXACO models—identify basic components of personality: openness, agreeableness, emotional stability/neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, plus, with HEXACO, honesty-humility. Then there’s the infamous dark triad of traits, comprised of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy (which stands in contrast to honesty-humility). Add everyday sadism for the dark tetrad.

Psychiatric models from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) identify several types of personality pathology: narcissistic personality disorder (PD), borderline PD, dependent PD, avoidant PD, schizoid PD, and several more. The DSM-5 also articulates a proposed model1 based on five maladaptive traits:

- Detachment

- Negative Affect

- Psychoticism

- Disinhibition

- Antagonism.

The Brain at Rest

With a fresh take, fascinating work from Cremona, Joliot and Mellet (2023) derived “thought profiles” from a cluster analysis of data from nearly 1,800 French university students. In addition to tried-and-true measures, this group completed a novel survey of resting-state personality dynamics, the ReSQ 2.0.

What is the resting state, or default mode, of one’s mind? Are we mellow or spinning with stressed-out worries? Is it overall negative, positive, or more neutral in there? What shape do our thoughts take if we observe them gently when letting the mind wander?

The ReSQ 2.0, a “multidimensional assessment of self-generated mental activity at rest,” has 24 main items2 characterizing baseline, mind-wandering mental activity.

Of the 24` ReSQ 2.0 items, 16 probe thought content, including experiences such as sense of time/timeline, body awareness, oneself, social thinking, the experimental situation itself, learning activity and emotional valence. Eight others stipulate thought forms: imagery, visual and musical; language and dynamics; tempo; and change. Thought has a timing and cadence, a symphony, even when humming along at the lowest conscious levels of wakefulness.

Established measures looked at psychological maturity, using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI); anxiety, depression, and overall trait negative affectivity—how much of a negative cast there is overall in one’s personality. How do the above factors interrelate over time, and what factors in the present may predict future emotional and psychological outcomes?

Six Thought Profiles

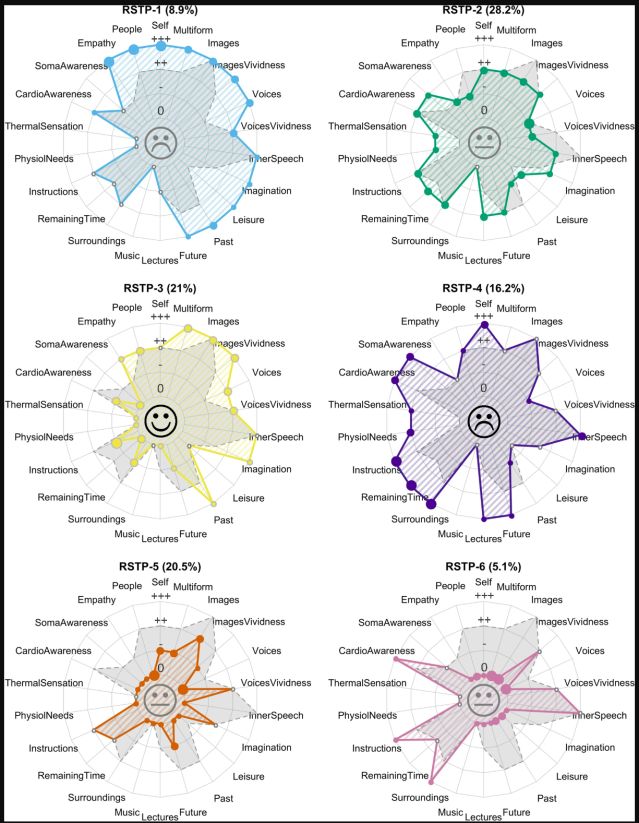

The analysis revealed six distinct profiles described and illustrated below. Graphically, each circle represents a singular thought profile, the spokes around a central hub representing different rating-scale scores. The overall emotional valence is represented by the center emoji. Each maps a distinct statistical cluster of mental activity derived from the personality types present in this sample; it is unknown how the results generalize to other populations.

RSTP-1 (9 percent). Emotions tended to be cast negatively. Participants thought very often about themselves and others with empathy, with inner speech and vivid images and voices. Very often such inner experiences were simultaneous. This profile associated with risk for depression and anxiety. Negative affect predicted greater psychological maturity, but only for those who reported lower overall maturity.

Personality Essential Reads

RSTP-2 (28 percent). This group showed neutral emotional tone. There was low or moderate resting-state scores overall, never at the high end. At any given time, individuals in this group reported having three or more themes running through their minds. This profile decreased the likelihood of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety.

RSTP-3 (21 percent). This profile had a positive emotional valence. Future thinking and inner thoughts were rare. Individuals in this cluster thought very often with both vivid images and voices about past events or fantasy. When they thought of people, which was not very often, it was with empathy. There was no clear relationship with maturity in this sample.

RSTP-4 (16 percent). This profile was negatively valenced. There was no specific link with empathy, images, voices, imagination, or relaxation. Thoughts were very often in the form of inner speech and ongoing sensory, reverie-oriented, and bodily sensations and needs. Negative affect predicted greater psychological maturity, but only for those who reported lower overall maturity.

RSTP-5 (20 percent). This profile had neutral emotional valence. Frequently, individuals in this cluster responded in the extreme low category on most resting-state items. Thoughts were sparsely detailed, only in the form of images, rarely about themselves or the future. There was a reduced tendency for depression and anxiety. Trait negativity predicted lower maturity.

RSTP-6 (5 percent). This profile also had a neutral emotional valence. The individuals in this group frequently responded in the extreme low category on most ReSQ items. They never thought in the form of images. They very often reported mulling over no more than three themes at a time, including heartbeat and breathing, the immediate environment, and the experiment instructions they’d received. Depression and anxiety were low. Negative emotionality was associated with greater maturity, but only for the most mature participants.

6 RSTPs

Cremona et al., 2023

What’s My Brainprint?

Experientially, this work is fascinating because it allows anyone to look at the ReSQ 2.0 items and self-reflect on their own thoughts and sensations; their orientation toward past, present or future; and to track the form and pattern of those thoughts over time. It proves a crude roadmap of the mind at rest.

Which thought profile an individual would be likely to be in was predicted to a significant extent by overall trait negativity, and psychological maturity shaped that predictive power. Four of the six profiles were associated with likelihood of anxiety and depression, especially RSTP-1.

Psychological maturity and emotional valence were shown to be reliably linked to thought profile. Many more detailed findings linked the RSTPs to factors including personality and disposition, subtypes of thought content and form, and dynamic patterns with RSTPs over time.

Without overgeneralizing from one study of French university students, imagine the value of having an accurate “brainprint” telling you useful things about yourself, what you are inclined toward, what would tend to improve your well-being or, perhaps, incline you toward illness. Applications of brainprinting could perhaps indicate whether specific thought profiles get along well, useful for relationship matching as well as group and organizational teamwork and leadership studies.

Pairing self-report with neuroimaging findings, which increasingly seek to draw conclusions from resting-state neural network activity for predictive and diagnostic purposes, will increase the power of this kind of analysis. Likewise, further development and testing with more diverse populations, and inclusion of measures such as standard personality tests, additional indicators of well-being and illness, attachment profiles, neurodiversity, developmental and environmental factors, behaviors, and outcomes will lead to greater validity and applicability, perhaps a true typology. Machine learning can also be deployed to search for persistent and predictive patterns in large data sets, amplifying the potential value of brainprinting.