This post is by David Preece, Ph.D., edited by James Gross, Ph.D.

How are you feeling right now?

You might find this question easy to answer, almost impossible to answer, or somewhere in between. We all have emotions, but it turns out that people differ in how well they can understand and express emotions. Way back in the 1970s, scientists invented a word for having difficulty understanding and expressing emotions, alexithymia.

Source: AbsolutVision / Pixabay

What Is Alexithymia?

The term alexithymia means “no words for emotions” in Greek. After 50 years of research, we now know quite a bit about alexithymia and why we need to be on the lookout for it.

We know that alexithymia is a trait that exists on a continuum—everyone has some level of alexithymia, whether that be a low, average, or high level. Around 10 percent of people have high enough levels of alexithymia that it causes problems. These people rarely focus attention on their emotions and have a lot of difficulty identifying and describing their emotions. People with high alexithymia still have emotions, it’s just that they tend to experience them in a more undifferentiated way—like knowing you are feeling bad, but being unsure if that negative feeling is sadness, anger, or fear.

Why It Matters

This undifferentiated “soup” of emotion is a problem because emotions are important parts of our lives. Different emotions tell us different things, but if they all seem merged into a confusing mess, we are at a big disadvantage.

Emotions are very important for our well-being, and being able to regulate emotions is essential for good mental health. We now know that there are many ways to manage or regulate emotions and that some strategies are better suited to certain situations and emotions. People high in alexithymia have less accurate information about their emotions, and consequently struggle much more to manage them—they are at much higher risk of mental health issues, like depression and anxiety disorders.

Emotions are also very important for relationships. If we don’t understand our own emotions, it’s harder to understand other people’s emotions too, and if we can’t express our emotions, it’s harder to build the emotionally intimate connections key to close relationships. Our partner might think we “don’t care” or “just don’t get it”.

Fortunately, alexithymia levels are not set in stone, we can get better at understanding and expressing our emotions.

A Snapshot of Your Alexithymia Levels

You might like to get an estimate of your current level of alexithymia. Below are six questions from a measure our group developed, the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire. Rate each question based on how much you agree or disagree the statement is true of you – rate them on an answer scale from 1 (strongly disagree), 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, to 7 (strongly agree):

- When I’m feeling bad (feeling an unpleasant emotion), I can’t find the right words to describe those feelings.

- When I’m feeling bad, I can’t tell whether I’m sad, angry, or scared.

- I tend to ignore how I feel.

- When I’m feeling good (feeling a pleasant emotion), I can’t find the right words to describe those feelings.

- When I’m feeling good, I can’t tell whether I’m happy, excited, or amused.

- I don’t pay attention to my emotions.

Add up your scores for all six questions, this is your alexithymia score. If you scored 27 or more, your score is in the high range, suggesting difficulties understanding and describing feelings. If you scored between 11 and 26, your score is in the average range. If you scored 10 or less, your score is in the low alexithymia range, suggesting strong emotional awareness.

Seeing Your Feelings More Clearly

Let’s say we want to reduce our levels of alexithymia. How do we do that? One key ingredient is to improve our knowledge about emotions. Let’s learn a bit about them now.

Emotions have multiple parts to them, we experience them not just in how we feel (for example, the feeling of fear), but also in how our body reacts physiologically (for example, increased heart rate), and in our behavior (for example, fearful facial expression, an urge to run away).

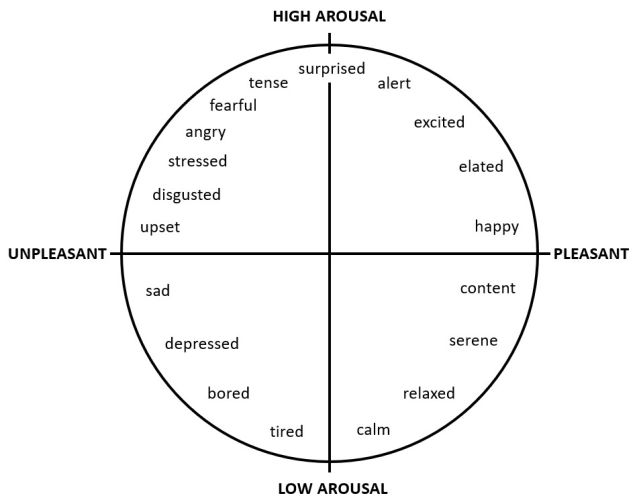

There are also many different types of emotions. Scientists don’t always agree on exactly how many there are, but one common model for organizing emotions is called the “circumplex” model. According to this framework, emotions differ across two main dimensions – (1) how pleasant vs unpleasant they are and (2) how arousing (activating) vs non-arousing (deactivating) they are. For example, sadness and fear are both unpleasant, but fear is a high-arousal emotion and sadness is low arousal. The image below shows how a variety of emotions can be mapped across these pleasantness and arousal dimensions.

Source: David Preece

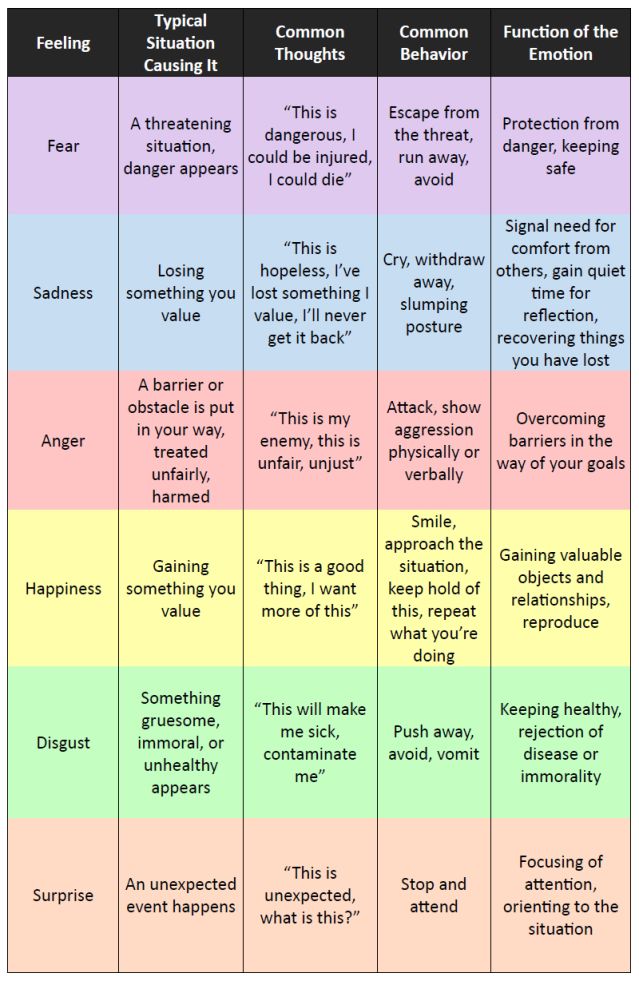

Different emotions can also be understood in terms of the different types of situations that usually cause them, the different types of thought patterns that characterize them, common behaviors, and the function of the emotion. These are summarized in the table below for six common emotions.

So, when you are trying to understand what you are feeling, be a detective, you can use these features as clues to see what emotion fits best:

Source: David Preece

Lastly, another way to reduce our alexithymia levels is to try to stop avoiding our emotions. People high in alexithymia often had childhoods where they learned to deal with emotions by not focusing on them, and suppressing them. Sometimes we do need to distract ourselves from our emotions, as they can get overwhelming, but if we are always avoiding them, that causes problems. It’s about finding the right balance.

To improve our emotional awareness and find that balance, it’s helpful to find safe people in our lives to practice talking about our emotions. This can be tough at first but becomes more natural over time. Just like gym training builds up our physical muscles, practicing thinking about emotions builds our emotional muscles—so we can start to see our feelings even more clearly, and in turn, harness the many benefits that brings.

David Preece, Ph.D., is a Clinical Psychologist and the Director of the Perth Emotion and Psychopathology Lab at Curtin University in Australia. Preece is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology.