A French philosopher named Michel de Montaigne described his anxiety and worry: “My life has been full of terrible misfortunes, most of which never happened.” This quote captures the core of worry: the recurring expectation that dreadful or catastrophic events will occur in the future and the implicit belief that worrying may help prevent them from happening.

Worries Often Don’t Come True

Scientific evidence suggests that most of our worries don’t come true. LaFreniere and Newman (2020) tracked the worries of people with generalized anxiety disorder (whose main characteristic is persistent, difficult-to-control worry about various topics) and how often their worries came true. They found that, on average, people had 34 distinct worries in a 10-day period and that 91.4% of worries did not come true in a 30-day period. That’s the average. The most common number reported by the participants was 100%, meaning that 100% of a given person’s worries did not come true. That’s not to say our worries never come true. Sometimes they do. However, in this study, even when the worry did come true, 30% of the worries were better than expected.

This research touches upon two of the main aspects of anxiety: exaggerated expectations of the likelihood that our worries (i.e., our feared outcomes) will come true and the severity of those feared outcomes if they do come true (Berenbaum, Thompson, & Bredemeier, 2007; Berenbaum, Thompson, & Pomerantz, 2007; Dev, et al., 2024). Interestingly, when we believe our feared outcome’s severity is high, we often overestimate the likelihood that the feared outcome will occur (Berenbaum, Thompson, & Pomerantz, 2007).

For example, imagine there are two jars in front of you, each with 100 pieces of candy. You get to choose whether you want to eat one randomly selected piece of candy from each jar. In each jar, 1 piece of candy is poisoned. In the first jar, the piece of poisoned candy is mildly poisoned; if you happen to eat it, you would just have a minor stomach ache for 30 seconds. However, in the second jar, if you happen to eat the poisoned candy, it will be very severe, likely fatal. You can choose to eat candy from jar 1, jar 2, both, or neither. How reluctant are you to eat one candy from the first jar? How about the second jar? The odds of getting poisoned from either jar are objectively the same: 1%. However, subjectively, does it feel like the likelihood of getting the poisoned candy is greater in jar 2 than jar 1 (i.e., if the candy’s poison is severe vs mild)? Probably. In fact, in two studies I conducted with my colleagues (Zbozinek, et al., 2021), we found that, when making decisions, aversion to risk, loss, and ambiguity increase as the financial value of the decisions increase. In other words, when the stakes are higher, we make more cautious decisions.

Why Do We Worry?

If worry tends to bias our predictions regarding the likelihood and severity of potential negative future events, why do we worry, then? There are a couple reasons. First, people who worry tend to have both positive and negative beliefs about their worry, and the positive beliefs are the ones that maintain worry (Borkovec, Hazlett-Stevens, & Diaz, 1999; Borkovec, et al., 1983; Köcher, Schneider, & Christiansen, 2021; Wells, 1995). The negative beliefs are that worry is uncontrollable, unpleasant, and harmful. The positive beliefs include that worry prepares you for negative outcomes and prevents them from occurring. How often do you worry because you believe it will help prevent problems in the future? Second, worry is an avoidance strategy. In addition to trying to avoid future negative outcomes, worry is a verbal process that reduces physiological activation (Hoehn-Saric & McLeod, 2000; Llera & Newman, 2010). When worrying, we engage in thinking about things, which reduces our physical feelings of anxiety or fear. This means that it feels better to worry than to feel afraid or anxious, so we sometimes worry to reduce the emotional experience of fear and anxiety.

Additionally, as I discussed in a previous post, fear and anxiety are elicited by situations that we believe are dangerous in some way, and they motivate us to protect ourselves from the danger or avoid it. In line with this, one theoretical and mathematical model of anxiety states that elevated anxiety is associated with excessive avoidance far in advance of potential danger (Zorowitz, Momennejad, & Daw, 2021). The idea here is that if danger can successfully be avoided later, there is no reason to avoid it now (and there may even be costs to avoiding it now, like missing out on enjoyable aspects of life, or engaging in stressful, effortful actions to avoid the danger). However, anxious people are more likely to avoid the danger far in advance of threat, which can lead to misplaced reliance on early avoidance, exaggerated beliefs of danger, and generalization of fear because the person thinks they need to avoid early and often. This could lead to worry and anxiety in safe situations, which is excessive, unpleasant, and can interfere with daily life.

Furthermore, because worry is associated with excessive avoidance, it’s important to remember that worry has costs. It costs time, effort, and emotion. It can also have relationship costs: For example, people who dislike uncertainty often worry and seek reassurance from trusted people (Clark, et al., 2020). In small amounts, reassurance-seeking might be fine, but excessive reassurance-seeking can strain relationships (Halldorsson, et al., 2016; Shaver, Schachner, & Mikulincer, 2005). Reassurance-seeking also leads to a reliance on others in order to feel safe and disregards or reduces a person’s ability to cope with problems on their own. Worry can also have financial costs (e.g., a person who has worries about their health may excessively reach out to healthcare professionals, therefore incurring unnecessary healthcare costs).

Problem Solving: The Healthy Alternative to Worrying

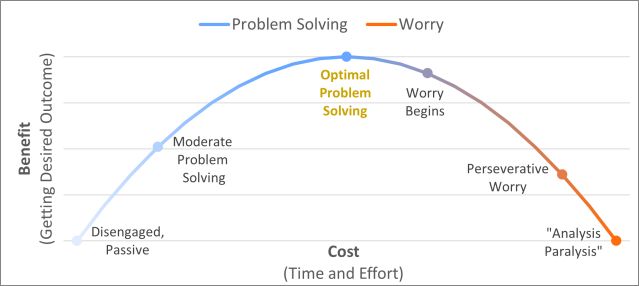

If worrying is so costly, what can we do instead? The main alternative is problem solving. Both worry and problem solving aim to fix current problems or prevent future negative outcomes. Worry is perseverative and associated with difficulty tolerating uncertainty (Koerner & Dugas, 2008), whereas problem solving is much more time- and effort-bound and effective. (See Figure 1 for a conceptual illustration.) People who worry will search for more and more information related to their problem, seeking a solution and trying to obtain certainty that the decision they are making is the best one. Doing your research to figure out a viable solution is helpful (an aspect of problem solving), but with worry, the information-gathering process is unbounded and stretches beyond what is helpful. The problem of worry-spurred information gathering is that the more information you find, the more likely the pieces of information are going to conflict with each other, which spurs further information gathering. This leads to a lot of time and effort seeking something impossible: certainty about the future and certainty that the choice being made is the best one. It also leads to “analysis paralysis”—being overwhelmed by all the information and indecisive about how to proceed. Even if a person comes up with a viable solution while worrying, they will probably keep iterating excessively over the problem and the solution, like they’re stuck in an infinite loop.

Figure 1. Problem Solving vs Worry: The Cost-to-Benefit Ratio

Source: Tomislav D. Zbozinek, PhD

In contrast, problem solving is much more efficient and concise. It does require some time and effort, but the time and effort shouldn’t be excessive, and problem solving generally yields beneficial results. Problem solving involves defining the problem, thinking of solutions, picking a solution, enacting the solution, and moving on (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2010). If there are natural waiting periods while enacting the solution (e.g., waiting for a specific event to occur or to hear back from someone), a person who is worrying will keep thinking about the problem (without making much progress), whereas a person who is problem solving will work on something else constructively (or engage in enjoyable aspects of life).

So, How Do I Stop Worrying So Much?

The first step is knowing the difference between problem solving and worrying, as described above. The second step is mindfulness, which is non-judgmental awareness of the present moment. Be mindful of when you are worrying. This means consciously catching yourself when you worry. A helpful way to do that is to notice when you are feeling anxious. Notice that you’re feeling anxious, and ask yourself, “What was I thinking right before I felt anxious or while I was feeling anxious?” This will help you identify the worrisome thoughts. Third, in line with cognitive behavioral therapy, worries are thoughts, and thoughts may or may not be accurate, and they may or may not come true. Remembering this when you notice your worrisome thoughts can take the edge off the thoughts because, even though it can sometimes feel certain that worries will come true, it doesn’t mean they will. Fourth, shift from worrying to problem solving, engaging in a more limited, intentional, and directed thought process to develop a solution, enact the solution, and move on. This can spare you heartaches and headaches, all while helping you more effectively achieve your goals. Lastly, learn from this process. Did problem solving effectively help you achieve your goals? Was it more pleasant than worrying? Did any negative outcomes occur because you engaged in more time-limited, effort-bound problem solving instead of worrying? Did positive outcomes occur? With repeated practice, can you let go of worrying and instead make problem solving your default?

Reducing worry can sometimes be difficult. For people who worry a lot, worry might be habitual, happen without your awareness, and be very resistant to change. This is normal, so keep chipping away at your worry and trying to replace it with problem solving. As with most aspects of anxiety, worry can be nuanced, so addressing it would require understanding those nuances and targeting them appropriately. If you feel like you would benefit from additional help, consider reaching out to a competent therapist for support; they can usually help you identify beliefs or patterns of thinking that contribute to your worry and help you worry less.

To find a therapist, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.