You wonder what lurks in those shadows outside your window, down the hall, in the corners, or beneath your bed. Dangers exist, you know that. Vigilance helps you survive by alerting you to risks, but it can also keep you trapped. Excessive preoccupation with potential danger, hypervigilance, interferes with truly living life. At the other extreme, insufficient concern or responsiveness to risk, hypovigilance, can lead you right into the monster’s jaws. To help you find and walk the ever-shifting line in between, you mentally and emotionally rehearse your fear responses in safer settings and times.

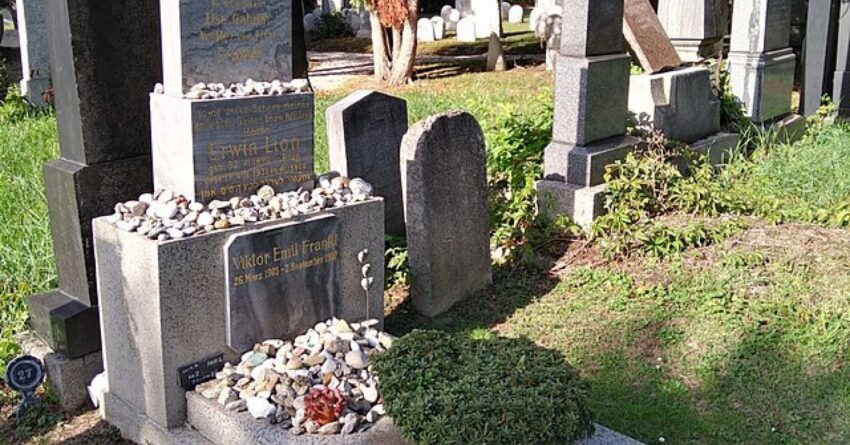

Grave of Victor Frankl. Vienna Central Cemetery.

Source: HannaH30, Wikimedia Commons, shared under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0.

Existential psychologists suggest that human beings’ awareness of our fleeting mortality will motivate most choices we make and things we do. We want to make life worth living in the moment, to keep ourselves alive, and to find ways we might continue to exist beyond physical life. For psychologist Viktor Frankl (1946-1947), who later spread existential psychology throughout the world, many of his ideas about this grew out of his years surviving the horrors of Auschwitz and other concentration camps. To keep ourselves going, we want our fear and pain to matter. We dread the idea of suffering for nothing. Frankl concluded that we do not simply try to find meaning in life. Instead, to survive and even thrive, we feel driven to make it mean something.

In a modern, more scientifically-based spin, terror management theory suggests that the mental conflict over desiring life versus knowing death’s inevitably creates the terror that we continually work to control (Greenberg et al., 1986; Solomon et al., 2015). In this line of thought, death anxiety not only makes us seek to extend life and hope for afterlife, but it also guides and empowers nearly everything we do: We want the symbolic immortality of leaving an impression upon others, having an impact in the world, and knowing it will matter that we were here. Spiritual beliefs may arise from the need to believe we exist beyond the grave, but so might reproductive and creative endeavors. Terror management theorists say the terror never really leaves us, therefore we do what we can to work with it rather than drown in it. More than a hundred years ago, psychologist William James (1902) paved the way for Frankl and the rest when he called the knowledge that we must die “the worm at the core” of human existence.

When you read a horror novel, watch a spooky movie, or tell your own scary story, you are making an affirmative choice: You will face that worm, not hide from it or flee. You will practice your hereditary survival response in manageable ways so that you might strengthen yourself and overcome the worm’s power to hurt you: You exercise to exorcise. It’s just as true when you follow uncanny poetry, such as that of Edgar Allan Poe, through one eerie line after another. Even reading a poem, essay, or relevant article on this website helps you work with the worm rather than against it, because even the freest, most unstructured verse transforms abstract terror into concrete text.

Instead of letting terror crush you, you share a spooky story because it lets you mount the worm and maybe nudge it to take you where you need. You do not simply walk that tortuous line between the extremes of vigilance. You ride over it.