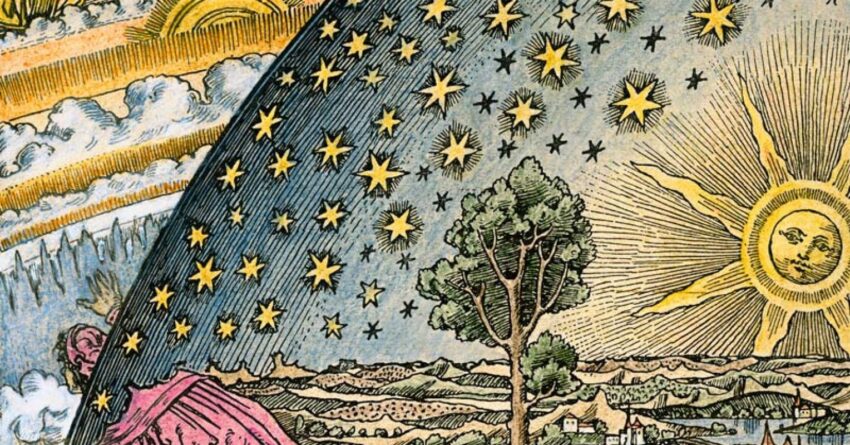

Source: Flammarion Engraving, artist unknown/Public domain

“No progress was ever made except by those who were willing to take their noses off the grindstone of details and take in the bigger picture.” — Albert Einstein

I recently visited Ellis Island, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, which for over 60 years was America’s busiest port of immigration.

Among the Ellis Island Immigration Museum’s vast audio collection is a tape my great-aunt made of my family’s life in czarist Russia at the dawn of the 20th century, which helped explain why my mother once insisted I watch Fiddler on the Roof. “It’s our family’s story,” she said.

In listening to my great-aunt’s voice, I heard part of my own creation story recited by an elder I never knew, helping me place myself in a far deeper, richer, and wider context: reminding me that I’m much more than what the philosopher Jean Houston calls my “little local story.” In fact, we’re each part of something vastly greater than ourselves, an endlessly unrolling tapestry that preceded us by hundreds of years (millions, actually) and that will proceed without us for millions more, but that includes us.

The reason I was so moved by my visit to Ellis Island—and the glimpse I got there of a story much bigger than the one I view through the knothole of my individual life or the “current events” that backdrop it—is that lately I’ve been feeling consumed by the dramas of my little local story, epitomized by my fixation with the November election.

I find myself routinely down in the weeds with it, wringing my hands. I pore through every microscopic detail of it, from half a dozen different news outlets every day, denounce myself for not doing and donating more, and forget a basic principle of consumer culture: While I consume it, it consumes me, gobbling up my precious time, depleting my emotional reserves, and occasionally devouring my initiative.

I also feel a little ashamed that the sacrifices my ancestors made to get to America have become the freedom I routinely exercise to worry myself sick over the daily news.

Granted, there’s great utility in being able to put my nose to the grindstone, my shoulder to the wheel, and my ear to the ground—it gets things done and helps me make sense of the world—but in the long run, it’s not a terribly comfortable position.

And given the stress many of us feel in our daily lives (whether in relation to the current election cycle, the cost of groceries, or the world in its present shocking condition), the ability to occasionally take a giant step back from it all, and take a deep breath, becomes a potent coping mechanism if not survival mechanism—even if, by doing so, we end up scolding ourselves for stepping out of the bucket brigade while Rome burns.

But the bigger picture reminds us that Rome has always been burning and always will, and even if you cast yourself in the role of brother’s keeper, all soldiers occasionally need shore leave. Life’s not a fire we’re going to put out.

One of the essential characteristics of perspective is distance from whatever’s pressing in on us, because the closer we are to a thing, the more we’re entangled in its intricacies and the less we truly see of its dimensions. “The health of the eye seems to demand a horizon,” Ralph Waldo Emerson once said. Thus we need something to counter nearsightedness, unhook us from the tyranny of details (and polls), and encourage us to think bigger and remember our relative position in the colossi.

That something could be the study of history, geology, mythology, cosmology, or spirituality, or simply being with people in a deep rather than frivolous way, because the moment you strike up a meaningful conversation with another person—perhaps especially with someone from the other side of the aisle—you’re getting outside yourself and docking with the wider world.

It could be the enormities of the natural world, which may be our most accessible vehicle for experiencing transcendence and contemplating metaphysical superlatives like infinity and eternity. Turn fossils over in the palm of your hand; gaze through an observatory telescope at Saturn and its rings; stroll down the aisles of any vast library; press your nose to the glass of a diorama at the museum of natural history that shows heavy-browed hominids standing at the edge of a forest and staring out across grasslands that will one day be the skyline of a city.

It could be retelling the story of your life as a myth or fairy tale, starting with “Once upon a time….” You would become the hero or heroine, and your earthly struggles recast as plot twists in an epic adventure. You’d see the big picture of your life, the way it might look from the press box on Mount Olympus where the gods sip mint juleps and watch The Game.

It could be wandering the streets of a city come and gone, since ruin-wandering shows us that all empires—personal, civic, and mythic—eventually come tumbling down.

Or it could be an imaginative exercise like this one from the British scientist Richard Dawkins: Spread your arms wide. The tip of your left hand marks the beginning of evolution and the tip of your right hand marks today. The span from the tip of your left hand all the way to your right shoulder brings forth nothing more than bacteria. The first invertebrates make their entrance near your right elbow. The dinosaurs appear in the middle of your right palm and die out near your outermost finger joint. Homo erectus and Homo sapiens appear at the white part of your fingernails. And all of recorded human history would be erased by the single stroke of a nail file.

To be sure, these kinds of investigations can be a bit like waving ammonia under your nose because among the challenges of submitting yourself to the big picture is that the individual is more or less lost to sight. But this can be quite redemptive. The ability to put things in perspective is a master skill capable of showing you what really matters and what doesn’t, what’s worth spending your precious time on and what isn’t, and what’s within your control and what isn’t.

Gazing up at any good-sized cliff, for example, whose sedimentary layers display huge slabs of time—epochs, not calendar pages; eons, not the latest poll—you face the unavoidable fact that your individual life, your entire generation, your whole civilization for that matter, are one day going to be a thin strip of sediment in the side of a cliff. This actually ought to be a relief because in terms of anything you might fear failing at and so avoid—or overwork yourself in order to avoid—you might take comfort in the fact that failure is already assumed. You’re going to die and be a million years dead, and anyone who might possibly judge you for your failures and fixations is going to be a fossil right next to yours in that cliffside.