We yearn to be connected to others.

Developmental psychologists tell us we’re born with nonverbal behaviors that pull caring responses from others that help us to survive. As we grow older, if we are to continue to have our physical and emotional needs met, we learn additional ways to invite others to connect with us in nurturing ways.

At least that is what is supposed to happen. But something has gone wrong recently.

Despite being surrounded by technology promising to make it easier to link ourselves with others, more of us feel lonely now than ever before. Even before the pandemic began, surveys showed that nearly half of adults in the United States complained that they lacked companionship, felt that their relationships were not meaningful, saw themselves as isolated from others, and no longer felt close to anyone. When the pandemic hit, it made what already was a bad interpersonal situation far worse.

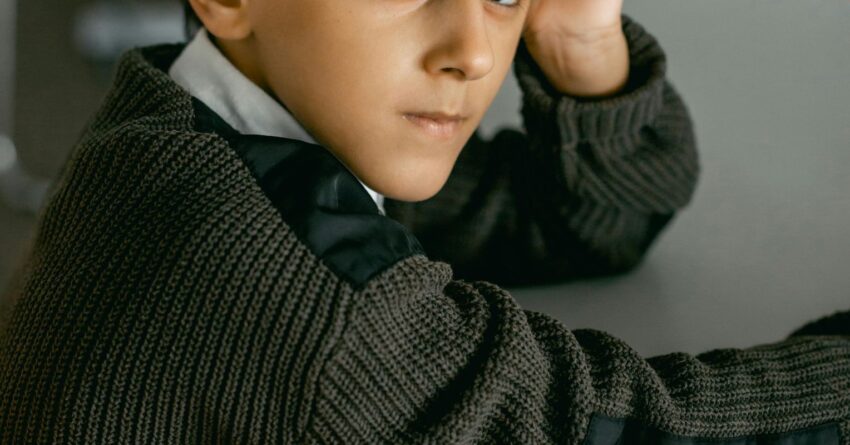

Children are lonely too. The National Survey of Loneliness showed that children between the ages of 10 and 12 were the loneliest of all, a finding all the more dismaying because loneliness in children has been clearly linked with the development of psychopathology such as anxiety, depression, and suicide.

Why are we failing at connecting when we want and need to be with others so much? Regardless of how rich, accomplished or intelligent we are, most of us believe that our happiness is tied to having successful relationships.

How did connecting with others become so difficult? In a way, relationships seem simple enough, don’t they? We choose others, to begin with, and then we get to know them better and use that information to decide whether we want to go deeper to find out whether they could be a friend or a romantic partner.

But the big question is what information do we need to gather. And what do we gather it from to successfully move from one phase of a relationship to the next?

The answer is that we must communicate with one another to “greet, meet and go deep.”

But here is where things get more complicated, because to make interpersonal progress, we must be competent at two “languages.”

The first language is one we all are well aware of, the use of words in verbal language. The other language, nonverbal language, which includes cues conveyed by facial expressions, tones of voice, postures, gestures, personal space, touch and rhythm, is not always as apparent to us.

While both languages are needed to connect with others, nonverbal communication is uniquely constructed to have a significant impact on relationship development. Not only does it operate below our awareness, but it is also always “on.” Even when we stop using words, our faces and bodies continue to send cues of how we feel, whether we want them to or not. Putting that together with the fact that when verbal and nonverbal language differ in what they communicate, we tend to believe the nonverbal message, it becomes apparent that a lack of skill in nonverbal language could have a continuing and unrealized negative impact on our interactions.

Research supports this assumption. Lower nonverbal communication skill has been related to a wide range of negative outcomes associated with relationship difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, and social rejection as well as loneliness in children and adults—outcomes that have all increased dramatically during the past decade.

We need to be as skilled in nonverbal as well as verbal language if we want to be successful in forming close relationships. But here’s the problem: Unlike verbal language that is formally and directly taught in school, nonverbal communication is learned indirectly and informally through interaction with others in social situations.

Unfortunately, the interpersonal time usually available for the learning of nonverbal communication has been stolen away and increasingly spent on screens. The pandemic accelerated this process by further isolating us and forcing us to deal with one another even more extensively via a variety of technical devices.

Loneliness Essential Reads

As a result, we have had less opportunity to learn the nonverbal skills necessary for us to connect with one another and successfully navigate the choice, beginning, deepening, and ending of relationships. The consequence is that we may be less able to send and receive nonverbal information accurately, increasing the likelihood of mistakes that interfere with our attempts to connect with others—leaving us and our children frustrated and lonely.

If this is true, we need to become more skilled in the use of nonverbal language. We can do this in several ways. One is to spend less time on screens and more time with others in face-to-face interactions. Another is to teach it in the same way we teach verbal language, by direct and formal means. Both may be useful to increase our nonverbal competence.