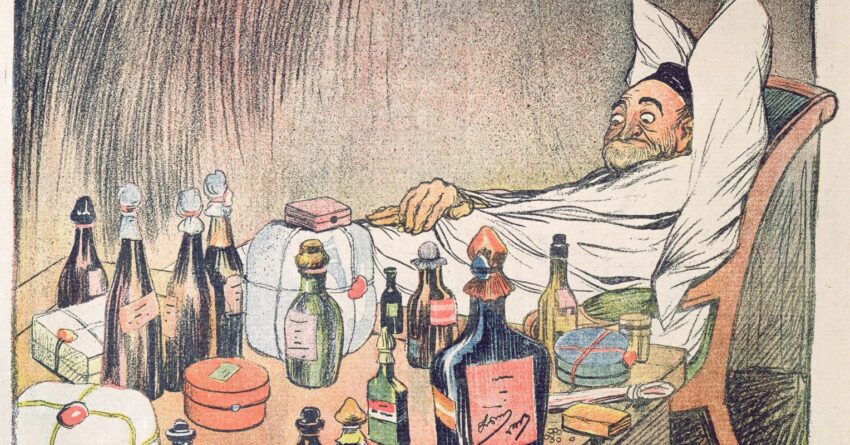

“Le Malade Imaginaire,” an image based on Moliere’s play, is a 19th-century painting by Honore Daumier in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Seeing himself “infirm and ill,” Argan, the imaginary invalid in Molière’s comedy of the same name (1673), insists, for purely selfish reasons, that his daughter marry a physician. By doing so, Argan would have “good assistance” with his own illness and have, at his disposal, all the “remedies, consultations, and prescriptions” he might need. Within one month, for example, Argan has taken “twelve remedies and twenty enemas” prescribed by his physician, who seems little more than a quack.

Even Argan’s own brother sees Argan as “no man who is less ill.” His brother believes in having nature take its course. He says, “It is our anxiety, our impatience, which spoils all; and nearly all men die of their remedies, not of their diseases.” He ultimately suggests that Argan become a physician himself, “…there is no complaint so daring as to meddle with the person of a physician.”

And, of course, becoming a physician involves no more than donning a cap and gown, such that “any gibberish becomes learned…” The play ends with Argan preparing for his initiation.

Molière “skewers” the medical profession, explains his translator. In his satire, all the physicians are caricatures. In Argan, Molière may be parodying his own anxieties about health and his own experience with the limited knowledge of physicians of his era. Significantly, Molière suffered from ill health for much of his life, and this play was his last. He was only 51 when he died (van Laun, 2004). Suffering from health anxiety did not necessarily prevent an early demise, especially in the 17th century.

What do we know about health anxiety? The 5th edition of our Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) eliminated a previous category from earlier editions of somatoform illnesses and now created two categories: somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder.

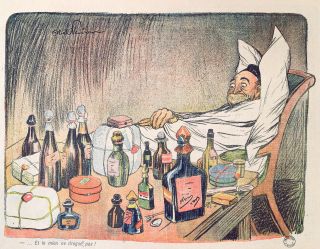

“The Abuse of Medicine,” by French artist Jules Abel Faivre, 1904. Like Argan in Moliere’s play, many with health anxiety will take unnecessary medications and undergo unnecessary work-ups.

Source: Copyright Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

Those patients with somatic symptom disorder suffer from distressing bodily symptoms accompanied by persistently and disproportionately high levels of anxiety about health as well as abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to their symptoms. They often present in medical rather than psychiatric settings. These bodily symptoms are seen as unduly threatening and can be specific (e.g., localized pain) or non-specific (e.g., fatigue). About 75% of those previously diagnosed as hypochondriacal are now subsumed under this category. A focus on their symptoms can assume a central role in their identity.

The remaining 25% of those previously diagnosed as hypochondriacal have “high health anxiety” in the absence of somatic symptoms or with very minimal ones. When physical symptoms are present, these are often normal physiological sensations or transient bodily discomfort. These patients with illness anxiety disorder have a preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious undiagnosed illness, with health anxiety along a continuum. Some patients are care-seeking and use medical facilities frequently for diagnostic work-ups. In contrast, others are care-avoidant and refrain from visiting physicians for fear of learning of some dreadful diagnosis (Kikas et al., 2024).

These two DSM-5 categories also eliminate the word hypochondriasis, with its pejorative connotation and sense of stigma.

Author Carolyn Crampton, a self-proclaimed hypochondriac, embraces the term in her beautifully written new book, A Body Made of Glass (2024). Says Crampton, “Hypochondria deals in contradictions: it is a perceived disease of the body that exists only in the mind.” She believes that those with hypochondria are fragile and vulnerable, i.e., breakable, like glass.

Hypochondria is “treated as an illness requiring quotation marks,” i.e., as a joke or something ridiculous, explains Crampton. It is considered a “shameful” condition, and she adds, somewhat ironically, that you never find it mentioned in an obituary.

Literary descriptions of hypochondria date back to the Babylonians in the second century B.C. Hippocrates used the word hypochondrium as a geographical term for a part of the body, says Crampton.

“The Hypochondriac,” by 19th-century English artist Thomas Rowlandson. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Source: Copyright Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

It was not until the 18th century, though, that a shift occurred, and the term acquired its mental component. Being vigilant of possible harm or contagion to the body, says Crampton, has evolutionary adaptive value, but when the vigilance becomes hypervigilance, it is no longer adaptive.

Virginia Woolf once bemoaned that illness has not been a popular subject in literature as love. She wrote,” Why has the ‘daily drama’ of the body not been recognized?” “Perhaps,” she adds, “Illness is almost impossible to communicate.” (On Being Ill, 1930).

Crampton disagrees with Woolf and has found “literature overflowing with accounts of sickness.” But it may be that it is hypochondria that is impossible to communicate adequately. Crampton notes that telling the story of any illness involves editing out the most frightening or embarrassing parts. She finds hypochondria is “plotless, a deviation from the regular progress of illness from stage to stage.”

Hypochondria Essential Reads

Her own hypochondria developed, as it does for some patients, after a recurrence a year after her initial diagnosis, at age 17, of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and a need for a second course of treatment. Crampton describes poignantly that, in retrospect, a photo taken of her before that initial diagnosis clearly showed the cancerous mass in her neck. The implication, of course, is that had she been more observant and vigilant, she might have caught her cancer earlier.

Now that diseases can be detected at a cellular level, the potential for anxiety about one’s health can become so much greater: “It is legitimately possible to have a verifiable condition without yet exhibiting any symptoms,” Crampton writes.

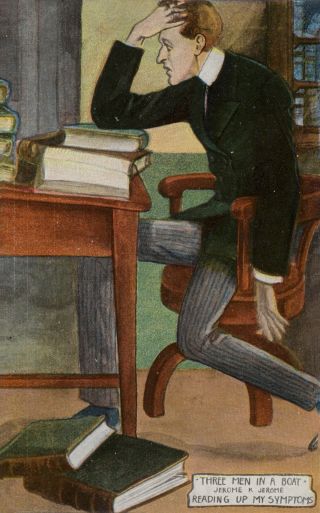

What can develop is that an “obsessive desire for knowledge” itself becomes a symptom, made worse in this age of internet access. There is even a term cyberchondria for those who obsessively search the internet to ease their anxieties about their health—only to find information that can make them feel more apprehensive (Jungmann et al., 2024).

“Reading up on My Symptoms.” English School, 20th century. Private collection. While some with health anxiety will search in books, more likely today they will obsessively search for information on the internet.

Source: Photo credit: Look and Learn/Elgar Collection. Bridgeman Images. Used with Permission.

Crampton suggests that the allure of Elizabeth Holmes and her company Theranos may be understood in the context of hypochondria—the desire to know what ails us immediately with just a drop of blood was so strong “an entire industry overlooked deep flaws in the science.”

Epidemiologist John Ioannidis alerted physicians to his suspicions about Theranos, subsequently known to be fraudulent, but not before it became a $9 billion company, even before journalists and the mass media got wind of Holmes’ deceit. He found no peer-reviewed scientific literature on the process, and the company acted in “stealth mode.” Ioannidis noted that Holmes focused on the fact that people should be able to order their own diagnostic tests as many and whenever they wished, with no mention of “overdiagnosis, false-positive findings, or the potential…for perhaps overly zealous diagnostic and screening efforts” (Ioannidis, 2015).

In his follow-up article, Ioannidis emphasizes that the “most troubling aspect” of a company like Theranos that “tries to push its agenda of massive personalized testing” is its failure to appreciate the “possibility of causing substantial harm” from widespread testing, “as errors accumulate with multiple testing” (Ioannidis, 2016).

For those who are care-seeking sufferers of hypochondria, the availability of widespread and sometimes misleading or even overtly incorrect information on the internet, as well as access to medical facilities for potentially unnecessary workups, can contribute to their health anxieties. Further, it is a disorder where reassurance, even from physicians, is short-lived (Espiridion et al., 2021).