According to the World Health Organization (WHO), clinical depression affects nearly 300 million people worldwide. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that 20 million or more people in the U.S. have depression at any given time, while more than 18 percent of U.S. adults report depression at some point in their lives and .more than 12 percent of adults report significant feelings of anxiety.

Treatment for depression is of limited effectiveness; only 30-40 percent of those initially treated experience full resolution of symptoms, or remission. What’s more, studies show, successive efforts to achieve remission are less and less effective.

Understanding the underlying biology of depression, anxiety, and related conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is necessary for making correct diagnosis and planning effective treatment. But especially in psychiatry, given the complexities of the brain, diagnosis and treatment are not yet well-grounded in biological understanding.

Medical treatment is ideally based on a number of factors, including knowledge of the disease process, the ability to make accurate diagnoses, and an understanding of how individual factors affect treatment planning and outcome. The National Institutes of Health started the BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) in 2013, calling for neuroscience-based models of disease and health. Understanding the causal factors of disease suggests the levers clinicians can manipulate to provide the most effective treatment possible.

Toward a More Scientific Psychiatry

Psychiatric diagnosis in the United States is currently based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Although efforts have been made to improve its approach with more specific criteria for mental illness based on statistics and available data, the DSM is not firmly scientifically based. For the vast majority of illnesses described, the diagnostic criteria say little to nothing about the cause of the disease; instead, they primarily reflect long-observed clinical patterns, rendering the DSM a work in progress and of less-than-desirable utility for diagnosis and treatment.

Not all causes of psychiatric disease are strictly biological. For example, inheriting a genetic predisposition to depression—and many genes contribute–does not invariably lead to depression. It’s highly likely that social and family factors can also bring on depression—not being productive or social, for example. Current treatments for depression often address biological and social factors, but there is as yet no standard biological testing for depression nor any clear framework for scientifically based treatment.

DSM 5 identifies several subtypes of depression, all based on clinical observation and statistical analysis. With unipolar depression (as contrasted with bipolar disorder), subtypes include atypical and melancholic, and specifiers include severity of symptoms as well as presence or absence of psychotic features. Diagnosis is made by reviewing clinical presentation and history, whether informally through clinical interview or formally via structured, guided interview and review of accompanying information. The same approach applies to anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety, social anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as to stress-related disorders such as PTSD. The disorders may be divided into subtypes by specifiers, but a true medical-scientific framework is lacking.

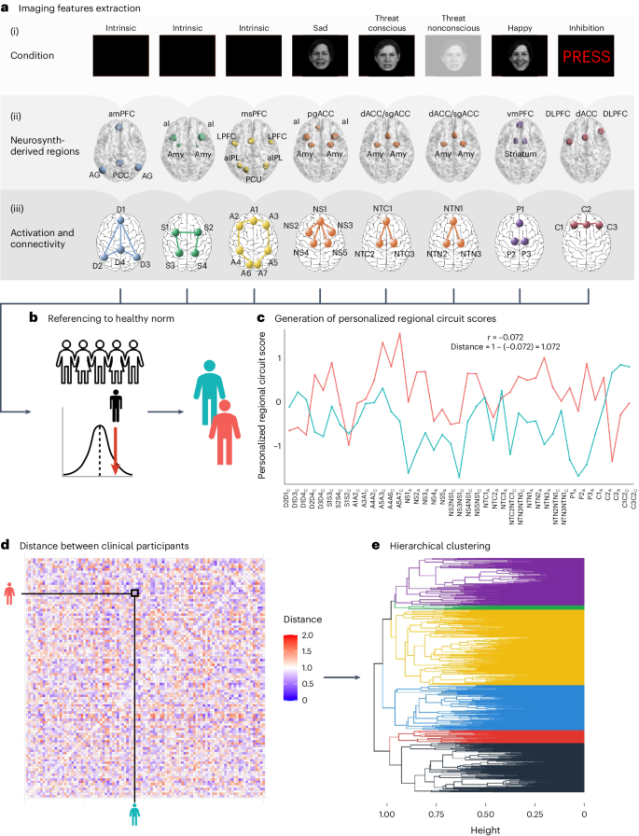

Biotyping Depression and Anxiety

A recent study of brain networks in depression and anxiety reported in Nature Medicine (2024) is an important step toward establishing an empirical model of “biotypes”,; it echoes prior work on depression3 and brain-based personality research4. Researchers Tozzi and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to look at brain activity in more than 1,000 people with depression and anxiety, measuring “task-free” brain activity. They repeated imaging in a subset of patients who received psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy or underwent a variety of activities. During the imaging, subjects were shown a variety of stimuli—such as sad, threatening, or happy faces—and were asked to perform a variety of cognitive and attention tasks. Cluster analysis was used to identify underlying biotypes based on brain circuit dysfunction, sometimes referred to as “dysconnectivity” in brain networks. Treatment would, therefore, restore “euconnectivity”.

Stimuli: Sad, Happy and Threatening Faces

Source: Tozzi et al., 2024 / Open Source

Notably, the study was transdiagnostic: Given how much depression an anxiety overlap, the study didn’t assume they are separate disorders. The analysis was unbiased by preconceived diagnostic models. Participants included those diagnosed with various conventional disorders, including major depression, generalized anxiety, panic disorder, social anxiety, PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder,. Some patients met criteria for more than one diagnosis.

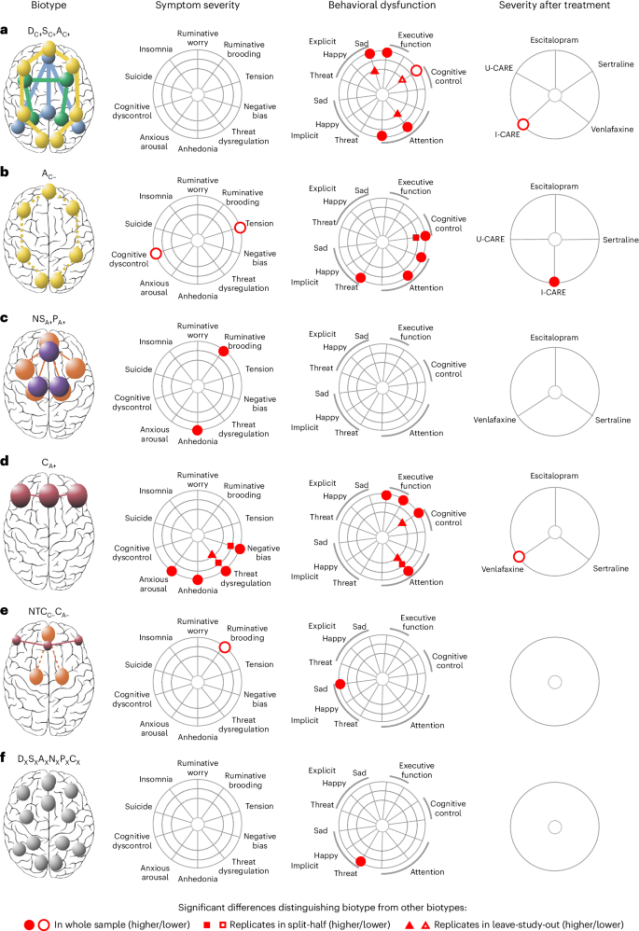

Six underlying biotypes of depression and anxiety were identified among participants with clinically-significant symptoms. Their labels are complicated, based on activity levels in key brain networks: default mode, or resting state (D); salience, or what stands out as important (S); and attentional (A). In addition to connectivity patterns, research looked at such key factors as negative emotional circuitry in response to sadness and threat (conscious and unconscious), positive emotion circuits, and cognitive circuits. There were no sex differences in response patterns, and minimal differences in age.

Depression Essential Reads

- Biotype DC+SC+AC+. This cluster showed hyperconnectivity among all three networks. This biotype had slow responses identifying sad faces and increased errors in executive function tasks. The response to behavior coaching for wellness was strong.

- Biotype AC−. This cluster had less connectivity in the attention network, less severe stress compared with other biotypes, and relatively little dysfunction in cognitive control, with faster responses on cognitive measures but more errors, as well as faster priming when viewing threatening faces. Response to behavioral coaching was less robust.

- Biotype NSA+PA+. This cluster had elevated activity during conscious processing of emotions, with sadness evoking greater negative circuit activity and happiness more positive. This group also experienced more severe anhedonia—inability to enjoy things—and greater ruminative brooding.

- Biotype CA+. This group showed increased cognitive control under specific conditions. This cluster also showed greater anhedonia, greater anxious arousal, negative bias, and dysregulation in response to threat. Cognitive errors were high, especially with sustained attention. This biotype had a better response to the antidepressant venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) commonly prescribed.

- Biotype NTCC-CA−. This small group was characterized by loss of functional connectivity in negative emotion circuits during conscious processing of threatening faces and by reduced activity in cognitive control circuits. This cluster had less ruminative brooding and faster reaction times to sad faces.

- Biotype DXSXAXNXPXCX. This small group did not show significant circuit dysfunction. There were slower reaction times to implicit threat.

6 Biotypes

Source: Tozzi et al. 2024, Open Source

Implications

While not ready for standard clinical use, the study results build on prior work demonstrating that brain network analysis holds promise for developing biologically based diagnostic testing for depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. The study also provides initial proof of concept that psychiatric biotyping could be used in the selection of treatments, with some biotypes responding better to medication and others to psychotherapeutic interventions.

Clearly, more work is needed before such models of illness can underpin diagnosis and treatment. Given the complexity of the human experience, it’s important to recognize that many of the causes of mental illness are likely to be social or circumstantial, external to the individual. More debatable is how to distinguish psychology from neuroscience, mind from brain, without becoming neuroreductionistic. Personalized scientific approaches to psychiatry on a par with other medical disciplines remain largely aspirational, but current approaches are likely to move the needle.