Traditional martial arts training with an emphasis on movement sequence practice is beneficial to those on the autism spectrum. I’ve long had an interest in this, initially born from my direct experience teaching karate to some folks on the spectrum. That martial arts practice is helpful is quite clear–why is less so.

Practice makes sense

A key feature of traditional martial arts training is repeated practice of predefined arm, leg and stepping movement sequences. These forms (kata, taolu, hyung) or patterns are the “DNA” of martial arts comprising sequences of defence and attack that can be excerpted and trained for self-defense. But the grounded core training for eventual use is rigorous and repeated practice of the forms themselves.

It’s been suggested that a contributor to sensorimotor performance on the autism spectrum is an issue of processing of the sensory feedback that occurs during movement itself. Our brains plan movements based on our prior experiences and a large part of this is related to the sensory feedback that occurred when we previously did the movements. Brains use this prior experience as a kind of template of what to expect with future movement.

What you want isn’t always what happens

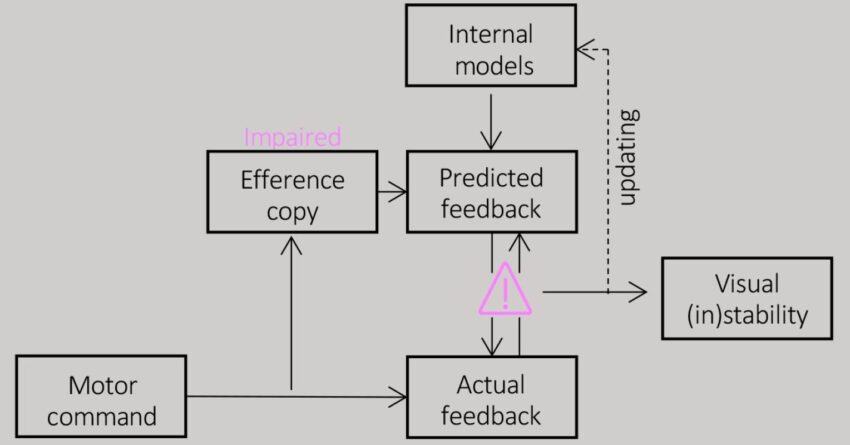

When we actually do a movement sequence, in martial arts or any other context, commands arise from the brain that make their way to the spinal cord which contain the cells that activate the muscle to make the limbs move. Simultaneously a kind of internal memo (efference copy in neuroscience lingo) is sent throughout the sensorimotor areas within the brain. This “memo” basically sets an expectation especially around anticipated sensation that should be coming back to the brain while the movement unfolds.

Your brain compares the actual feedback to that which was expected and based on what actually occurred, makes adjustments for subsequent movements. When there’s a big gap, this creates a need for immediate adjustment. This will also feel very uncomfortable because you are not achieving what you are trying to do.

Sensorimotor mismatch in neurodiversity

A recent study provides some mechanistic evidence that there are some differences in matching and processing of efference copy for neurodiverse folks on the autism spectrum, and likely beyond. Antonella Pome and Eckart Zimmermann in Dusseldorf, Germany were interested in testing “the idea that sensory overload in ASD may be linked to issues with efference copy mechanisms, which predict the sensory outcomes of self-generated actions.” Using a visual tracking task, they found that “those with more autistic traits had difficulty using information from their eye movements to update the spatial representation of their mental map” which resulted in errors in target finding. In a secondary experiment they also noted that those with “higher autism scores exhibited a greater bias, indicating under-compensation of eye movements and a failure to maintain spatial stability.”

This study is important because it clearly shows that efference copy is vital in sensorimotor stability and that this is likely altered on the autism spectrum. It must be noted that further research in folks who are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, not just who demonstrate “autistic traits”, is needed to establish the full relevance of this work to ASD.

Making martial use of mismatching

Ironically, actual martial arts applications are all about manipulating and deliberately creating a mismatch in outcomes and efference copy in order to defeat an aggressive attacker. If someone is punching you, their brain has already computed what their punch should feel like and when it should make contact with you. Anything that messes with the sensory feedback associated with that, messes up the movement itself and creates uncertainty.

So, if you move forward or offline, this is visual sensory feedback that is not expected. Or, if you deflect and guide the opponents punch past your head so the person is unbalanced, that is unexpected and creates a gap between what was planned and what occurred. At least in the attacker’s brain. If you are well trained in martial arts, this outcome from your movement is expected and there is no gap. Training is really about experience with so many examples of scenarios that even the most unpredictable outcome actually is related to prior practice.

(c) E. Paul Zehr (2024)