“There is nothing so patient, in this world or any other, as a virus searching for a host.”

―Mira Grant, Countdown

The gut-brain theory—how bacteria affect the brain and vice versa—now has a new player. To the 30 trillion bacteria living in our gut, add ten times as many viruses. That’s a frightening number of microbes to be hosting in the moist confines of our gut, especially if they have ill intent. Thankfully, many of them seem to be on our side, and in fact, some may help us deal with stress.

Source: Scott Anderson

If it is weird that tiny bacteria can affect our mood, it’s completely outlandish that far tinier viruses could do the same. And yet, they could usher in a new era of virus-based treatments for both gut and mental issues. The secret lies in the often brutal relationship between bacteria and viruses.

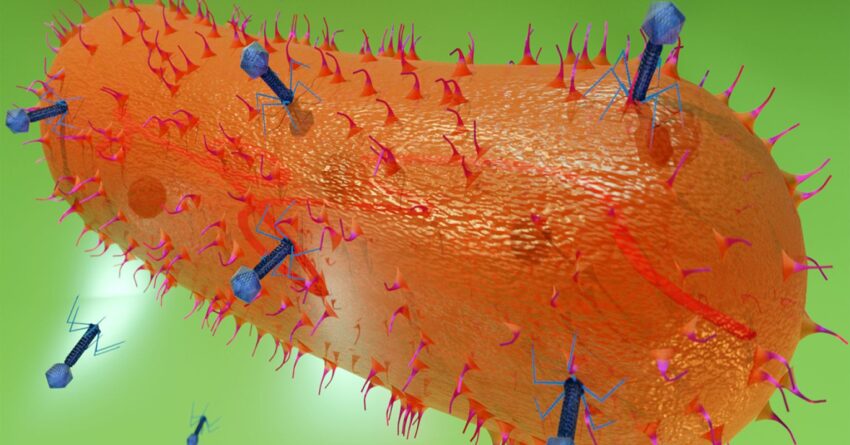

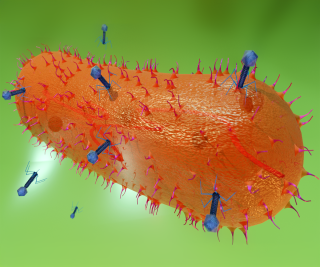

The viruses we are most familiar with are the ones that attack us. But viruses are not one-trick ponies; they can also attack bacteria. These are called bacteriophages, or just phages, Greek for devourer. This is actually a misnomer; phages don’t devour anything. To a bacterium, they are nightmarishly more insidious.

Not dead and not alive, phages lurk patiently for a bacterial host to infect. When they find one, they inject their genes into the bacterium and hijack its reproductive machinery to create more viruses by the hundreds. It doesn’t take long before the body of the bacterium is jammed full of phages. At some point, they can no longer be contained, and the bacterium explodes, spreading phages everywhere to continue their onslaught.

That is obviously bad news for the bacterium, but it may be good news for us if it was a disease-causing pathogen. In that case, the phage is a hero as it spreads out to kill specific pathogens, leaving beneficial bacteria unmolested.

In fact, phages are pretty particular: They are specialists that only have interests in a single species of bacteria. That makes phages a wonderful treatment for bacterial diseases, something we’ve known about for over 100 years.

Phages were one of the first tools in the war against pathogens, helping to treat avian typhoid in 1919. They arrived on the scene within a few years of the discovery of antibiotics.

But in many ways, phages are better than antibiotics. One dose is sufficient, since they grow and propagate as long as their desired host is available. They are thorough, killing every host in sight, but disciplined, avoiding any other bacterial species. And when the job is done, they simply get passed out of the system, where they will continue to wait patiently for their next unwitting host.

This being biology, however, there is another side to phages. Instead of multiplying, they can sometimes take up quiet residence without homewrecking. These are called prophages, and they entwine their viral genes with the bacterial genes. When the bacterium divides, the prophage genes are dutifully copied as well, and passed down to the daughter cells. It sounds cozy, but these are really genetic time bombs that can be triggered at a moment’s notice to enter their killing phase.

Researchers at University College Cork (UCC), led by John Cryan, Ted Dinan, Nathaniel Ritz, and colleagues, have shown that phages can also alter the response to stress—in mice, at least. To measure this, they first created a stressful environment for the mice by overcrowding them. That caused a measurable difference in their behavior, hormones, immune factors, and gut microbes—including phages.

Stressed mice tend to become antisocial and sometimes freeze in place, like a deer in the headlights. If that sounds familiar, it’s because humans have a tendency to do similar things under stress.

Then, to see if phages could improve the situation for these crowded mice, they collected some fecal pellets from happy, unstressed mice. They filtered the poop to extract the phages and then fed the phages to the crowded mice. After ten days, the mice that got the phages were noticeably less stressed according to both behavioral and biological measures. The phages had managed to restore the mice to a pre-stressed state, with lowered levels of anxiety and depression.

How does this work? Although the exact mechanisms are yet to be figured out, the ability of phages to kill potential pathogens and radically alter the bacterial landscape is a likely factor.

These are early days for the research. The exact phages that are restorative have yet to be fully defined. And of course, mice are not people. Although we have a lot in common with these small mammals, our bacteria are somewhat different. Still, this points to the collection of viruses in our guts—the virome—as another modifiable factor in helping us deal with stress, with the potential to create therapies that could someday be customized to individual patients.

When it comes to dealing with the ubiquitous stress of modern life, every bit helps, even extremely tiny bits.