Chess is best played calm.

Source: DALL-E 2024

Ancient Roman stoic philosopher Seneca said, “We suffer more in imagination than in reality.”

While he died in 65 AD, his words could not be more true now, two thousand years later.

Knowing If You Are Stressed or Anxious

There’s a difference between stress and anxiety, and knowing which is which can help you better understand yourself, as well as help you find ways to improve your life.

Everyone experiences stress. Traffic is stressful. Work is stressful. Having to do more than one thing at a time is stressful. One way to look at stress is that there is any time there is a mismatch between your ability and the demands in front of you. Stress happens at the moment.

Anxiety, on the other hand, can be based on real stressors, but it resides more in your head and not in the present moment as stress does. A key differentiating factor for anxiety is the degree of departure from reality into imagination. Stress is real, tangible, and here and now. Anxiety is a bit more of a story. It’s imagination. It can be exaggerated, obsessive, catastrophic, or even paranoid at times. Anxiety is able to cause worry and feelings of adrenaline, even when there is no real stressor happening at the moment.

How Imagination Plays into Anxiety

Imagination is a human superpower because it lets us think up things that are not real. It also lets us look back and reexperience the past, as well as plan and predict for the future. These are vastly powerful tools that make humans special, but they can be as much a blessing as a curse. For people with vivid imaginations, anxiety can channel in positive as well as negative directions. I often think of imagination, especially in the case of anxiety, as an “emotional amplifier.” Anxiety is an added layer on top of reality, on top of real-time stress, that often comes with a story, expectations, or fears, none of which are real or happening now.

When Is It Too Much Anxiety?

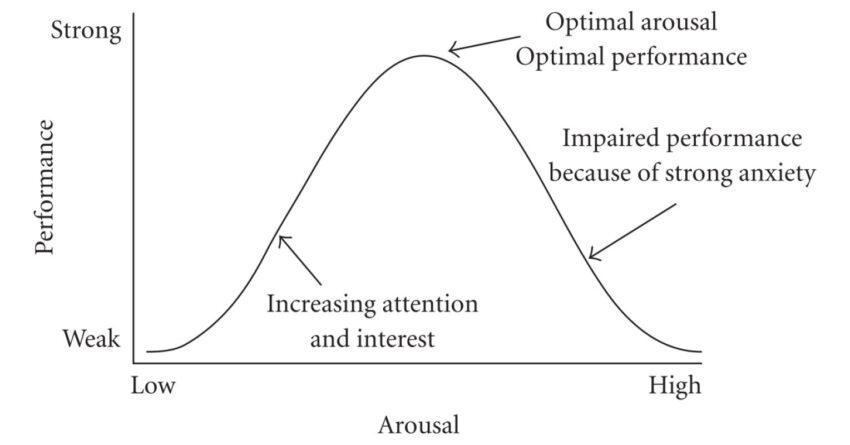

There is a lot of debate about how much anxiety is ideal. The Yerkes-Dodson law posits that the total absence of anxiety is not great, some anxiety is ideal, and too much anxiety hurts your performance. It’s an upside-down “U” shaped curve. However, this has been disputed, with the most recent findings suggesting that any anxiety is not good for one’s performance.

I often remind my patients that “chess is best played calm.” Getting nervous, flustered, and throwing pieces around the chessboard can be quite distracting from the actual game. Life is the same way. We might agree that some anxiety is good for motivation, but too much, and you get sloppy and lose track of the task at hand. This is a powerful lesson for many people who think they need to be anxious to perform well. It helps to start relating differently to your anxiety, especially from the perspective that it does not make you who you are or better and that it can be too much.

Getting a Grip on Imagination and Stories

The San tribe of South Africa is known to sleep with their ears to the ground so they can tell if a threat is real or in their dreams. We can learn a lot from that practice. Firstly, it helps to recognize when your mind may be dreaming or imagining too much. A clear sign of this is if the stories or “daydreams” that play out in your mind take up a significant portion of your day or are intense enough to get your heart racing.

With this awareness, it also helps to remember you will act more wisely from a place of peace rather than agitation and that “chess is best played calmly.” This starts with becoming aware of your imagination and the stories you tell yourself. The goal is not to stop them but to become aware of them and allow them to pass before making any big assessments or big decisions.

Another way to look at it comes from the couple’s therapist, John Gottman. While his work focuses on couples therapy, the relationship with yourself is perhaps the most fundamental relationship of all. Gottman writes about flooding. He says, “If your heart rate exceeds 100 beats per minute, you won’t be able to hear what your spouse is trying to tell you no matter how hard you try. It is physically impossible to communicate.” Indeed, ”chess is best played calm,” even with yourself.

When you feel adrenaline, an elevated heart rate, and a sense of urgency or agitation, this can be evidence that your reptilian brain has taken charge. Consider yourself effectively drunk at this point—and the aim is to be sober for the drive through any experience.

Keep an eye on this and know when it’s happening so that you can disconnect and take a break to cool off. The goal is to unplug from the problem long enough to cool off and get a new perspective. According to Gottman’s couple’s work:

- Breathe and practice mindfulness in the moment.

- Imagine yourself in your favorite place, a safe place, and get lost there.

- Meditate into that thought and place.

- Truly try to relax. Exercise or music is good.

- No ruminating, replaying the issue, or planning how to respond or get even. You really gotta let it go for the break to count.

Surrender and Accept to Calm Down

In couples work you are allowed to return to the issue once calm, which typically takes about 20 minutes or longer. In my work with patients with anxiety, I recommend taking an even longer break as the time constraints of couples therapy are not present. Sleep on it. But the key is to not dwell and obsess in the meantime. You really gotta let it go, to come back centered with a clear head, and make the best decision.

As I always remind my patients with depression or severe anxiety, “No big assessments and no big decisions” when you are stressed, tired, sad, angry, etc. Which is the equivalent of not driving drunk. Take a time out (and trust that this will really help) and come back with a fresh perspective. The art here is to trust and truly allow yourself a time-out to unplug from the issue and have faith that you will find a wiser answer from a place of healthy calm.

Equanimity: Definition: mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.

Source: DALL-E 2024

How Buddhists Get Things Done

A common view of Buddhism is one or surrender and acceptance of whatever is going on. But there is much less emphasis on taking action. Indeed, per Buddhist philosophy, the role of acceptance and surrender is only half of the solution. Acceptance and surrender allow us to return to a state of balanced equanimity (definition: mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.)

From this point of balance, you will be able to think most clearly, and take the most thoughtful, loving next step.

To get to this point, you will need to practice trust. Trust in yourself that you will make the best decision later from a point of calm. Then, trust your way into a place of calm and feel it. Before doing anything else. Don’t just do something. Sit there… and find a way to do so calmly. The right course of action will emerge from this place. All feelings come and go. Surrendering and allowing them makes it all that much easier. Take action only from a point of equanimity.