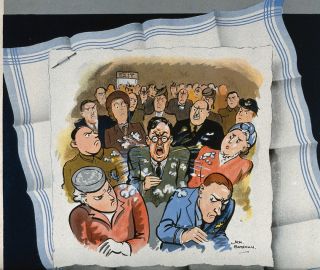

A man sneezing in a cinema, showing the use of handkerchiefs to prevent infectious disease, by HM Bateman, ca. 1951.

Source: Wellcome Trust Collection. Used with permission of Ms. Lucy Willis, granddaughter of Mr. Bateman / HM Bateman Designs

Aviation tycoon Howard Hughes instructed his staff to use six or eight thicknesses of Kleenex, “pulled one sheath at a time” to open a doorknob and a sheath of 15 to 20 fresh Kleenexes to turn off a spigot. “If you need both hands, use 15 in each hand.” Doors and windows had to be sealed with masking tape, and aides had to hand him objects wrapped in “paddles” of Kleenex (Bartlett and Steele, 1979/2004).

“Each day, he painstakingly used Kleenex to wipe dust and germs from his chair, ottoman, side table, and telephone.” Hughes spent hours meticulously cleaning, preoccupied with his “continuing skirmishes against contamination,” all to control the “dreaded flow of germs into his room” (Bartlett and Steele).

Over the years, Hughes ultimately developed a “breakdown of psychotic proportions,” vividly depicted in the 2004 film The Aviator (Bartlett and Steele). His biographers have described the quintessential, though extreme, germaphobe, i.e., someone with an excessive fear of and aversion to microorganisms (Robinson et al., 2021).

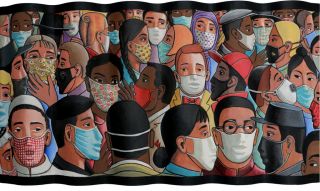

“Masque,” 2021, by PJ Crook/Private Collection. Tinted gesso on canvas on corrugated wood support.

Source: Copyright Pamela June Crook. All rights reserved 2024/copyright Courtesy of the artist/Robert Dandelson Gallery/Bridgeman Art Library. Used with permission.

We take the germ theory of disease for granted today: Handwashing is a significant part of a physician’s regimen. Most recently, during COVID-19, even though some questioned (and still question) the science behind the six-foot distance rule (Editorial Board, NY Times, 2024) or even the wearing of masks, no one seemed to quarrel with handwashing as one of the central tenets of public health guidelines to avoid the spread of the virus.

It was not always so. For example, women had been dying from puerperal fever at an alarming rate just after giving birth in one Viennese hospital during the 1840s. What was puzzling was only one hospital ward had these dire statistics. It took an astute clinician, Hungarian obstetrician Ignaz Semmelweis, to appreciate why (Ataman et al., 2013; Stang et al., 2022).

With the meticulous logic of an epidemiologist (Stang et al.), Semmelweis found that the unusually high death rate due to sepsis on that ward resulted from physicians who never washed their hands as they went directly from anatomical dissection to tending women in the delivery rooms. In another ward, midwives who did not dissect cadavers were more likely to deliver babies safely and less likely to expose the new mothers to infection (Ataman et al.).

These were the years before Louis Pasteur and surgeon Joseph Lister (Cavaillon and Chrétien, 2019). Semmelweis’s colleagues were unwilling to believe they had contributed to the deaths of their patients by infecting them with “cadaverous particles,” and they failed to adopt Semmelweis’s recommendation to wash their hands with a chlorinated lime solution before examining their patients. Obstetrical patients continued to die (Martini and Lippi, 2021).

“A wise woman brings a new one to a man whose wife just died.” 19th-century illustration.

Source: Bridgeman Images. Used with permission / North Wind Pictures

Semmelweis’s own story is one of the tragedies in the annals of medical history. Fired from his post, Semmelweis never garnered the recognition he deserved during his lifetime (Cavaillon and Chrétien). He died at age 47 in a mental institution (Noakes et al., 2007). His autopsy report indicated he suffered from injuries and infection sustained while being physically restrained (Cavaillon and Chrétien; Nuland, 2003).

Though we are more apt to use the colloquial term germaphobia, it was William Hammond, a 19th-century professor of “diseases of the mind and nervous system,” who coined the term from the Greek, mysophobia, a “form of mental derangement characterized by a morbid, overpowering fear of defilement or contamination” (1880).

Hammond’s series of 10 female patients demonstrated a “remarkable phenomenon.” They constantly washed their hands to remove “taints” and suffered from “delusions of pollution” (Hammond).

One patient reported,

“I washed everything I was in the habit of touching and then washed my hands. Even the water was a medium for pollution…there was no end to it…the soap became associated in my mind with contamination, and I never used the same piece twice.”

Another patient described, “by actual count,” washing her hands over 200 times a day (Hammond).

Hammond’s patients, though, were “conscious of the erroneous nature” and the “absurdity” of their ideas, but they could not refrain from their actions.

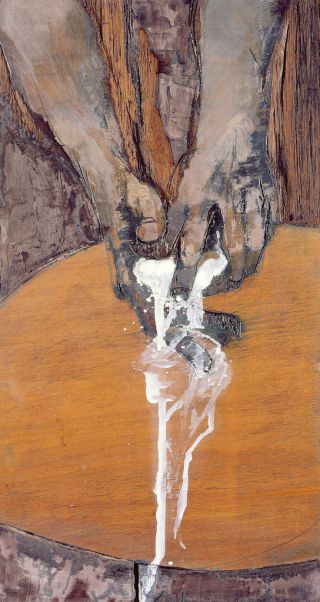

“Obsessive Compulsive-Cradle Soap I,” 2021, oil on panel by English Artist Olivia Reynolds. Private Collection.

Source: London/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission of artist Ms. Olivia Reynolds and Bridgeman Images / Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries

Though Hammond used the word phobia, and some might categorize a fear of germs and contamination as an anxiety disorder, many psychiatrists today would diagnose his patients as suffering from a full-blown obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is a neuropsychiatric disorder (Singh et al., 2023) characterized by time-consuming, distressing, recurrent, and persistent intrusive thoughts and urges (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors a person is driven to perform (compulsions) in response to the anxiety created by the obsessions (DSM-5 TR, 2022).

There is a continuum of severity, with some patients demonstrating insight and mild symptoms, while others (e.g., the severely incapacitated Hughes) lack insight and appear overtly delusional. Of note, though, I could find neither germaphobe (first used, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in 1894) nor mysophobia in DSM-5-TR.

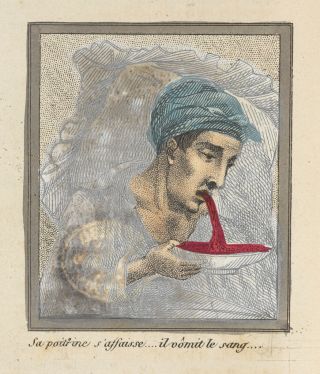

The most common symptom in those with OCD is a fear of contamination, and there is some suggestion that those who suffer are more apt to have strong disgust reactions as a means of protecting themselves (Mathes et al., 2019; Olatunji et al., 2004) from their “illusion of vulnerability” (Rachman, 2004). For more on the emotion of disgust, see my post.

“His chest collapses…he vomits blood…” Feelings of disgust at images of vomiting are often protective to avoid contamination from disease.

Source: British Library, London, UK from the British Library Archives / Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

Ritual handwashing, a common enough response to a fear of contamination, has been referred to as the Lady Macbeth syndrome (Lewis, 1997), named for Shakespeare’s protagonist. After Lady Macbeth has conspired with and incited her husband to kill King Duncan, her attendant tells the doctor that she has found her handwashing for “a quarter of an hour.”

Says Lady Macbeth as she is sleepwalking,

“Out, damn spot! Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him? Will these hands ne’er be clean? All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.”

Upon hearing this, the doctor tells the attendant, “This disease is beyond my practice.” And the doctor adds, “Unnatural deeds do breed unnatural troubles: infected minds…” (Macbeth, Act V, i).

Here, “physical and moral purity” are “psychologically intertwined.” Research studies have confirmed what Shakespeare knew intuitively: “Moral indiscretions” may pose a moral threat and stimulate an actual need for physical cleansing” (Zhong and Liljenquist, 2006).

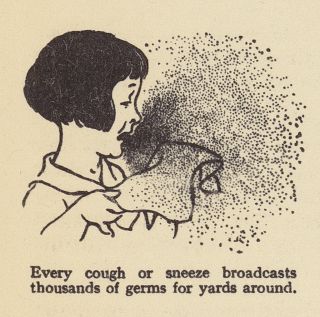

Germs broadcast by sneezing and coughing (lithograph). English School/20th century. There is often a fine line between excessive concern for health and appropriate measures to control the spread of germs.

Source: Bridgeman Images. Used with permission / Look and Learn

The importance of cleanliness in avoiding infection cannot be overemphasized. Still, there is a fine line between caution and an excessive, irrational preoccupation with germs and disease, i.e., health anxiety (Thorpe et al., 2011). Safety precautions recommended during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, generated considerable anxiety about remaining healthy in some vulnerable people. These precautions increased “contamination-related symptoms” (Samuels et al., 2021) and obsessive-compulsive preoccupations, though not necessarily full-blown OCD.