Sisyphus (1548–49) by Titian

Source: Image Bank of the Museo del Prado/Public Domain

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus speaks of the divide that exists between what human beings want and what the world offers. “The mind’s deepest desire,” he writes, “is an insistence upon familiarity, an appetite for clarity.”

Yet the “world in itself is not reasonable.” It will not satisfy our nostalgia for unity. It will not yield to our demand that everything make sense.

Human beings are meaning-seeking creatures. Our minds perceive a complex web of cause and effect at work in the world around us and, as a result, we expect to find causes everywhere.

Often, our expectations are met, and we discover the origins of events that at first seemed chaotic. This is the brilliance of the scientific method—it teaches us to work backward from what we experience (the data of sense perception) to what we can only perceive indirectly (the events that gave rise to that data in the first place).

And, yet, because we have become accustomed to perceiving order, we often project it, devising explanations where no explanation resides. When some unexpected calamity strikes, we fall back on clichés. We say that “Everything happens for a reason” or that “The universe has a plan.” When a loved one dies, we insist that “She’s in a better place” or that “He’s finally at peace.” When a relationship ends, we say “There are more fish in the sea,” and when we fail to achieve our goals, we insist that “No door closes without another one opening.”

If we find such platitudes reassuring, that is because they implicitly satisfy our desire for life to make sense. The world, they suggest, is rational. It can be understood. It can be subdued. Our lives are not subject to chance occurrences that arise out of nowhere and befall us for no reason at all. Blind chaos does not dictate our fate. Things will work out for us. There is a plan.

Source: Natalia Trofimova/Unsplash

But ask yourself: What is the meaning of a stubbed toe? What lesson is imparted by a spilled drink or a set of misplaced keys? Why is there such a thing as a hangnail? What is the logic behind it? What is the point? If everything happens for a reason, what, then, is the reason for papercuts? What is the purpose of the myriad pains, tediums, indignities, and inconveniences that go into making up our daily lives?

Or, more to the point, what significance can be gleaned from the suffering—excruciating and inexhaustible—that has been born by the poor and downtrodden of this world from time immemorial? What order can be deciphered in an existence that includes such things as starvation, disease, mental anguish, and death?

This confrontation between the irrationality of the world and “the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart” is, according to Camus, the cause of life’s absurdity. Were we not beings who pine for explanations, we would not feel the profound discontent characteristic of the human condition. But we do feel it. We wrestle with it every day. Human existence is marked by an absurd rift between what we expect and what we get. We want what we can never have and are befuddled when our desires are stifled.

What, then, can be done about the absurdity of our situation? How ought we to live?

For Camus, the crowning achievement of human existence resides in our ability to speak honestly about our predicament without falling back on illusions or evasions. To remain lucid, to “Call things by their name,” he says in his 1946 address “The Human Crisis,” is the first step toward overcoming the despair that often accompanies the realization that our deepest longings will remain unfulfilled.

More than that, such honesty represents a rebellion against the impotency of our position. When we admit our fate and yet refuse to succumb to it, we free ourselves from the anxiety denial can provoke. As the Camus scholar Jean-Luc Beauchard writes, “Meaning is born out of man’s conscious revolt against the meaninglessness of existence.”

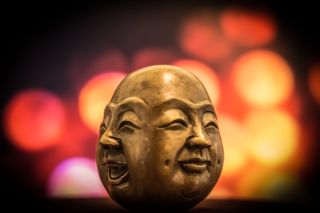

Two Faces of Buddha

Source: Mark Daynes/Unsplash

Is such an affirmative resolution not its own kind of illusion? Does not the belief that one could, by honesty alone, transform the experience of the absurd from degrading to exultant represent one more desperate grasp at wish fulfillment?

Yes and no. Camus famously ends The Myth of Sisyphus by saying of his absurd hero: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Imagination is of course the realm of illusion and make-believe. And, yet, such an admonition gestures at something profound. For Nietzsche, art takes trauma and refuses to stay with the traumatic moment as trauma but sublimates it into something else: tragedy. Camus, building upon this insight, suggests that tragedy, honestly assessed, can give rise to comedy.

The human condition is absurd, and that realization is intensely painful. But seeing it for what it is, Camus says, is the first step on the road to happiness. “What! by such narrow ways–?” he asks. Yes, if along with honest lucidity, one learns how to laugh.