Source: johnhain / Pixabay

Can you imagine someone saying, “Hey, Will, forget Hamlet, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet? Give us more Much Ado About Nothing.” Nobody would tell Shakespeare to stop writing tragedies and stick with comedies.

It’s the same when it comes to current treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). There’s a quickness to limit the range of a person with OCD, his creative mind and generous heart. For good reason. Who wants to live out a tragedy?

But there’s another way that protects the Shakespearean richness of the person living with OCD, tempering it so there’s less tragedy and more depth, dimension, and definition.

O, Brave New World That Has Such People in It

Are you convinced? Let me show you how to make this new world possible.

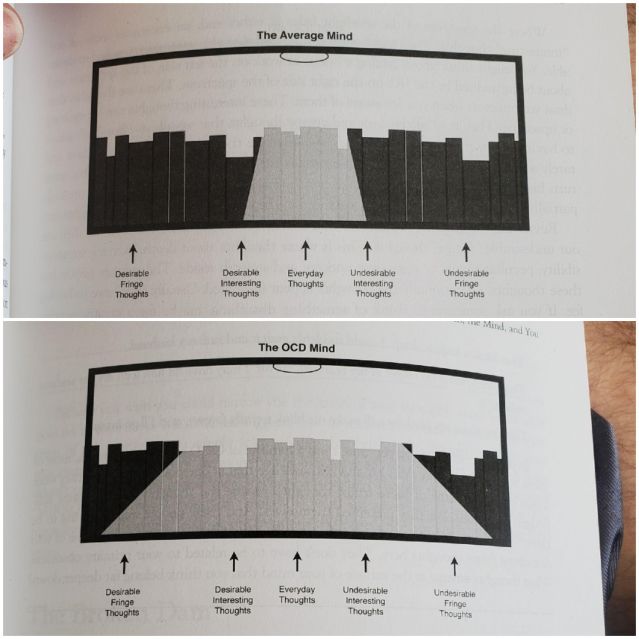

OCD advocate Catherine Benfield recently wowed me with the brilliance of the spotlight metaphor by OCD experts Jon Hershfield and Tom Corboy. The metaphor envisions the mind’s eye as a spotlight and a bookcase as the potential thoughts illuminated and examined by the mind’s eye. Books on the shelf are grouped from left to right as “Desirable Fringe Thoughts,” “Desirable Interesting Thoughts,” “Everyday Thoughts,” “Undesirable Interesting Thoughts,” and “Undesirable Fringe Thoughts.”

The average mind “brightly [illuminates] the books in the center, somewhat illuminating the books to either side of its beam, and leaving what may be additional books obscured on both ends of the shelf.” The OCD mind, in contrast, contains a beam that illuminates nearly the entire shelf.

According to Hershfield and Corboy (2013), “The problem with OCD isn’t that you overthink. It’s that you confuse the intensity, volume, or visibility of your thoughts with their importance.” Put another way, you’re too bright for your own good, which becomes a problem. Or does it?

One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure

This model highlights something unspoken but known by those who live with OCD: There’s more good stuff in there. A lot of people with OCD worry about admitting that as if it’s going to glorify the bad stuff.

Who wants to elevate the trash within OCD? But it’s possible to acknowledge both the good stuff and the bad, and in doing so, you’ll find the treasure.

If we retool the metaphor a bit, you can see why. Instead of imagining the spotlight as a fixed object, with proper treatment and support, those with OCD can learn how to shift the movement and focus of that spotlight without taking away any of its brightness and sweep.

One More Time with Feeling

Let’s enhance the spotlight metaphor one step further. In addition to the spotlight’s ability to move and pivot, let’s include something sorely missing from most cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approaches: feeling.

In contrast to Hershfield and Corboy (2013), who, as CBT therapists, prioritize thought, let’s add emotion. Suppose those books represent cognitive, imaginative possibilities alongside their emotional and dramatic possibilities. In that case, you begin to appreciate the range of people with OCD, their profoundly creative minds and generous hearts.

Feelings are not just the result of thoughts. They exist and operate in their own right and have their hidden logic. We know from current research, including the brilliant work of neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, that feelings have evolved with their innate wisdom and operate as a coequal branch of government inside the psyche.

As we reimagine the spotlight metaphor and CBT treatment, let’s not forget to include feelings. As they say in acting, let’s try that scene again—one more time with feeling.

What’s the Problem With Focusing on Problems?

The challenge that conventional treatments pose is that they attempt to solve the problem of the OCD mind by having it learn how to constrict itself better. Learn not to treat every thought with such equal importance and intensity, and you will become less plagued and more normal.

So what’s the problem here? It’s an either/or equation.

You can either be with someone with OCD, or you can be normal. While this is certainly understandable, given the most pressing desire of most people with OCD to get rid of their “Undesirable Fringe Thoughts,” it betrays the full humanity of those with OCD. It loses sight of the full range of what the OCD mind and heart are capable of.

Those capacities and powers don’t have to be lost, even with OCD treatment. You can transform the negative into nuance to keep the OCD full range alive.

This is a both/and approach rather than the current either/or approach to OCD treatment: Either you adapt to having a more “normal mind,” or you can’t expect to get rid of your OCD and be successful in treatment.

It’s possible to minimize the painful intensity of those “undesirable fringe thoughts” and allow ample room for all the desirable and undesirable interesting and everyday thoughts. This is part of what fuels both the personal and professional creativity seen in individuals with OCD from the more distant past, like biologist Charles Darwin and innovator Nikola Tesla, to the present day in climate activist Greta Thundberg, author John Green, and musician/producer Jack Antonoff.

This both/and approach enables and empowers individuals with OCD to benefit from their full Shakespearean scope.

There’s so much good stuff in this range that can help temper and soften the truly negative and challenging parts of OCD. Best of all, it can be accomplished without dimming the light of the OCD spotlight.

Why would you ever want to dim that light in the first place? As Jack Kerouac writes in On the Road:

The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or a saw a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.

Burn, burn, burn, not just with the madness of OCD, but with your beauty and brilliance.

To find a therapist, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.