We are built to reset from stress. Simple strategies like hugging help.

Source: AaronAmat/iStock

One of the most uncomfortable inner experiences we can have when we are in a state of stress is feeling “beside ourselves,” unable to connect with where we are. Whether we are in the midst of a panic attack, frozen in shock reading the news, heartbroken with grief, or immobilized with the stress of daily life, at the very time when we seem to be feeling so much, we also—paradoxically and disconcertingly—can’t grab hold of any feeling. The body seems to have a mind of its own and we are disconnected from it. Either we feel frozen like we can’t move, or are too agitated to sit still or commit to any task, going unsuccessfully from thing to thing in spirals of stress. In the throes of this seemingly out-of-body experience, we worry and wonder, “What’s wrong with me? Why can’t I just calm down and control myself?”

Nothing—I repeat, nothing—is actually wrong with us.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze: Our Body’s Automatic Response to Threat

The fact is, as uncomfortable and unsettling as those moments are, there is a very logical explanation for why we feel like we can’t think, concentrate, function, or even just sit still. We have gone “limbic.” Our wired-in sympathetic nervous system has detected a threat, and the amygdala, our inner alarm system, instantly shuts down our higher cognitive functions and shifts us into one of three gears: fight, flight, or freeze. We don’t get to choose. It happens before we can even assess what’s happening. Back in the days when we crossed paths with saber-toothed tigers, this was essential. These days, the protection can be worse than the threat. We can say to ourselves in a “top-down” way (from the brain to the body) that “nothing is happening now,” and that would be a good idea to do (find ideas more top-down ideas here), but thinking alone won’t override the amygdala hijack and its cascade of reactions throughout the body. The good news is there are simple strategies to switch gears, switch programs, and begin our recovery and reconnection with ourselves.

The Vagus Nerve—the Nervous System Reset—to the Rescue

Fortunately, we are built to reset: There are toggle points, “dimmer switches,” and nervous system “hacks” that we can intentionally engage to reset into recovery mode. We call them “bottom-up” strategies because they target the body, which then communicates to the brain that we are safe. The heaviest lifter in the reset is the vagus nerve, controlling 75% of the communication to our reset system—the parasympathetic nervous system (the “coast is clear” program, and the opposite of the sympathetic nervous system). This nerve is the longest in the body, meandering from the gut to the heart lungs to the brain (the Latin word vagus means “wandering”). When engaged, it’s our superhighway to calm. The heart rate slows, breathing slows, and we feel calmer. The more we practice specific toggles of the vagus nerve, the faster they work to switch us in and out of the states we need— it’s like a speed dial into the process of regulating our emotions and shifting back to safety.

Importantly, when we are in the midst of the amygdala hijack, we can’t remember what to do—that library of solutions is not “online” at that point. So, just like it helps to know how to change a tire before you find yourself by the side of the road with a flat, it helps to know what your options are for grounding yourself and bringing yourself back to center.

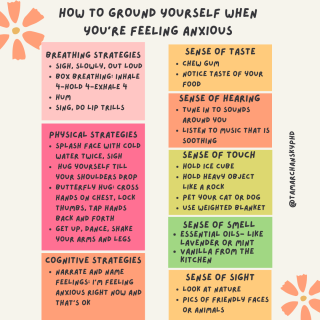

Strategy cheat sheet for grounding ourselves when we’re stressed

©TamarChanskyPhD

Bottom-Up Strategies: Learning Your Preferred Vagus Nerve Language

Control your breathing: We’ve all heard the advice to slow down and take a deep breath, and likely we’ve all dismissed that as too simple. But the fact is when we do the opposite of the shallow breathing of fight or flight, we are stimulating the vagus nerve and showing the brain we are safe. Each exhale resets the nervous system because we would never take the time to exhale slowly if we were face-to-face with the tiger. Here are some breathing techniques:

- Box breathing: Breathe in four, hold four, exhale four, and repeat around a box.

- Finger tracing: Inhale as you trace up your finger, exhale as you trace down the other side, repeat.

- Imagine you are blowing up a balloon (choose your favorite color). Take a deep breath and with each exhale visualize that you are releasing the balloon over a favorite scene—a tranquil beach, the Eiffel Tower, a field of flowers, or a mountain view. Blow up and release at least five balloons. Or, imagine there are letters on each balloon spelling the word calm, or center, or breathe.

Breathing a sigh (or hum, or lip trill) of relief: Ahhhhhhh, brrrrrrrr, rrrrrrrrhh, vvvvhhhh. Sound strange? The vagus nerve connects to the back of the throat, so even one good sigh also brings on an exhale and begins the reset to a calmer place. Humming, sighing, and lip trills (for non-singers, think of the sound we make to imitate a motor to a little child), singing harmony along to a soothing piece of music, the vibration goes from the back of your throat right to your heart, stimulates the vagus nerve and makes us naturally exhale—it may feel weird at first, but it works.

Cold exposure: After the cold comes the calm: We’ve heard the advice—go splash cold water on your face and you’ll feel better. But actually, there’s science to back that up. The sharp inhale we take when we are exposed to the shock of cold is followed by a long exhale—that is where we shift into parasympathetic recovery functioning. So whether it’s a 30-second cold shower, splashing cold water on the face, holding ice cubes, or putting them on your face, neck, or arms, it’s what happens after the cold shock that signals the recovery program in the body.

Give yourself a hug: “Can I have a hug?” We know that helps us feel better, and science backs up this most robust of armchair findings: With a hug, we release oxytocin. It’s not just “emotional,” it’s physiological. Our heart rate slows and we feel better. We can simulate those responses even if we are alone by giving ourselves a tight hug until our shoulders drop and we exhale—according to research, at least five seconds. We can hug a pillow very tightly. We can do butterfly hugs by hooking our thumbs together and spreading our fingers out so our hands are in the shape of a butterfly and putting our hands on our chest like wings and alternate hand flapping. A weighted blanket or even wrapping a regular blanket around you has a similar effect.

Go ahead and shake it off: We know that animals shake off adrenaline to calm themselves, and it works for us too. Shaking your arms and hands or legs for several seconds—or any kind of movement, even dancing—starts to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system and we begin to feel calmer.

We were built to cry: Despite the many negative associations imposed on crying, crying is a natural down-regulator of the nervous system. There is a reason we feel calmer after we cry: crying signals the parasympathetic nervous system, stimulates the production of oxytocin, and even releases toxins, so please let yourself cry.

Enlist your senses: Intentionally engaging your senses counters the fight-or-flight reaction and helps you feel grounded in the present. Here is the 5-4-3-2-1 strategy:

- Five things you can see: Look out the window, nature is calming, and so are the faces of loved ones or cute puppies or kittens.

- Four things you can touch: Take your shoes off and feel the floor, feel a fluffy blanket, pet your dog or cat, or hold polished stones in your hand or a stress ball.

- Three things you can hear: Listen for the sounds around you—the traffic, the whirr of a fan, the music playing, make sounds yourself like humming (see above).

- Two things you can smell: Keep essential oils such as lavender or peppermint nearby and notice how you exhale more deeply after smelling them. Other household scents can substitute, such as coffee, vanilla, perfume, soap, or a candle.

- One thing you can taste: Familiar tastes can be comforting, even if you are imagining them.

In stressful times, we can’t control what is happening “out there,” but we can begin to feel in control of ourselves by engaging in these practices. Having these strategies at the ready shortens the time that we feel disconnected from ourselves. Make it a mini project to find your vagal preferences and practice them in calmer moments over the next few weeks. That can help you have a stronger habit—you’ll trust that you can feel better, and that may give you a jumpstart on getting there. Here’s to peace and healing and less worry all around.

©2023 Tamar Chansky, Ph.D.